Wanted: Dead or alive? Distinguishing radiation necrosis from tumor progression after stereotactic radiosurgery

Images

Case Summary

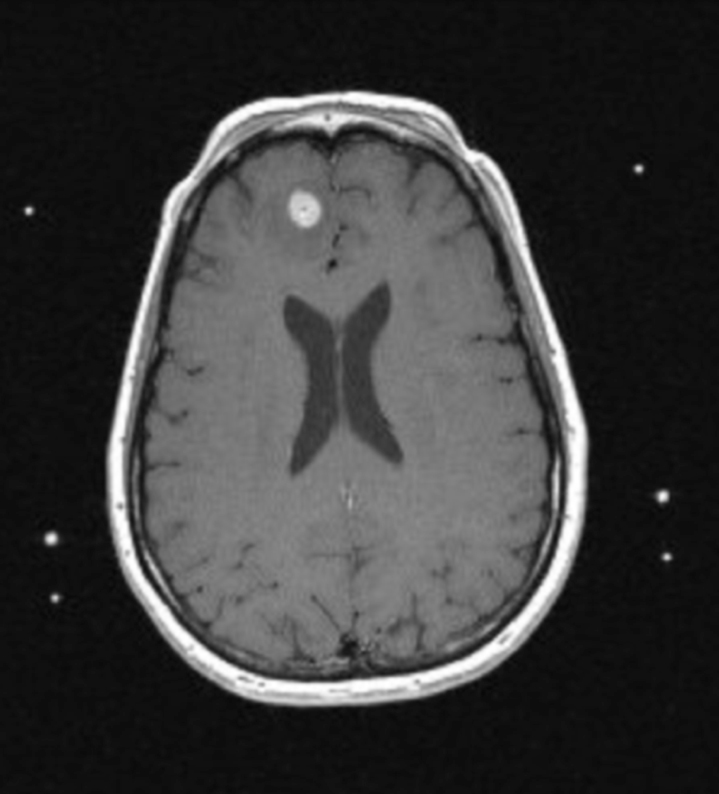

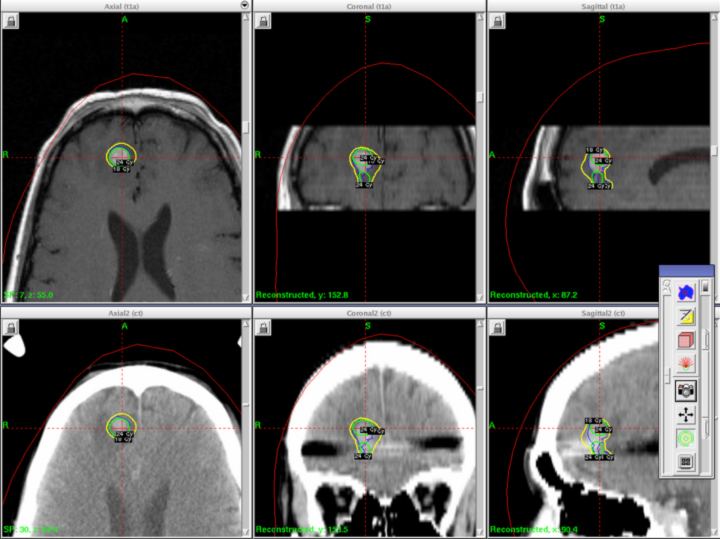

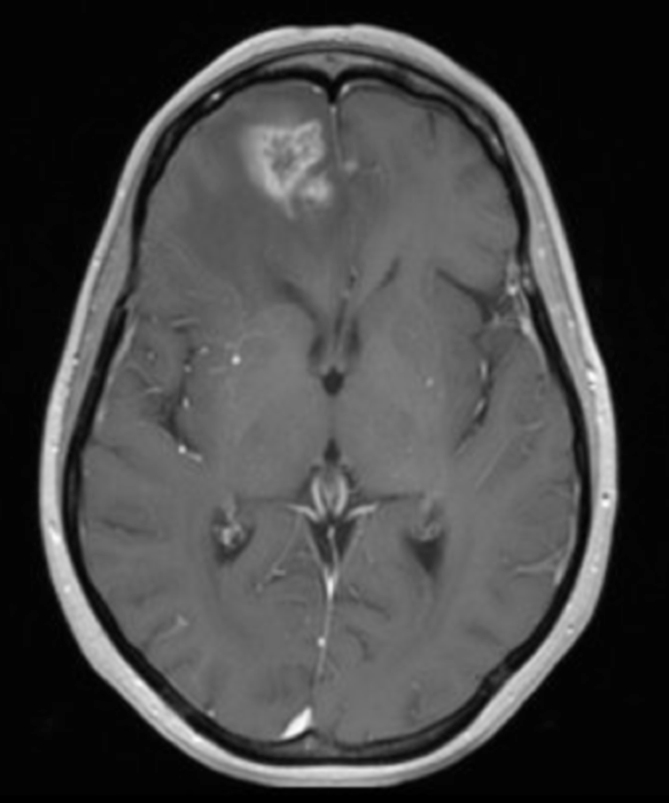

A 41-year-old woman with a history of melanoma 8 years prior to presenting was diagnosed with a right frontal brain metastasis measuring 1.0 × 1.0 × 0.9 cm (Figure 1). She underwent whole-brain radiotherapy to 37.5 Gy in 15 fractions followed by Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) (Figure 2).

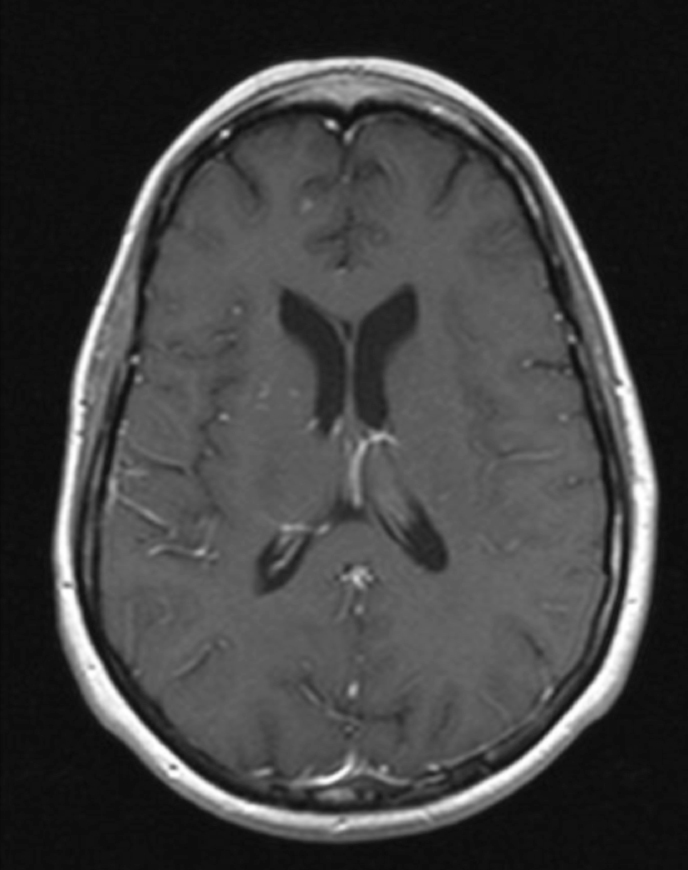

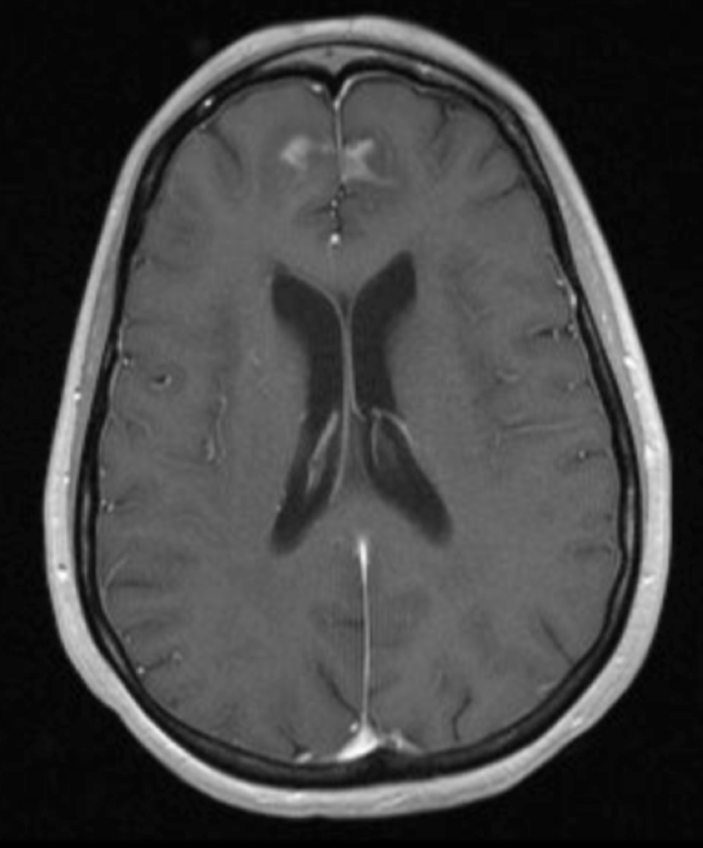

The lesion initially regressed, reaching its minimum size 7 months after SRS (Figure 3). Routine imaging at 10 months following SRS demonstrated enlarged contrast enhancement at the treatment site with extension into the left frontal lobe (Figure 4). Despite 2 courses of dexamethasone over 8 months, the lesion enlarged to more than twice its original size (Figure 5). Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and perfusion imaging were obtained (Figure 5). The patient was never symptomatic.

Resection of the lesion for diagnosis and management was performed 18 months after SRS. The patient is currently without evidence of active disease 43 months after initial SRS.

Imaging Findings

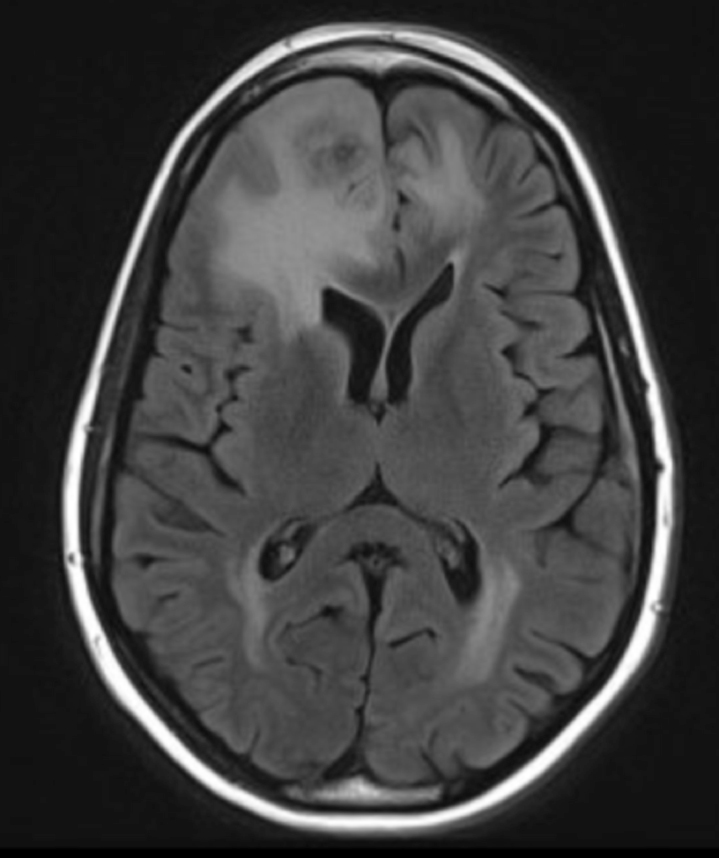

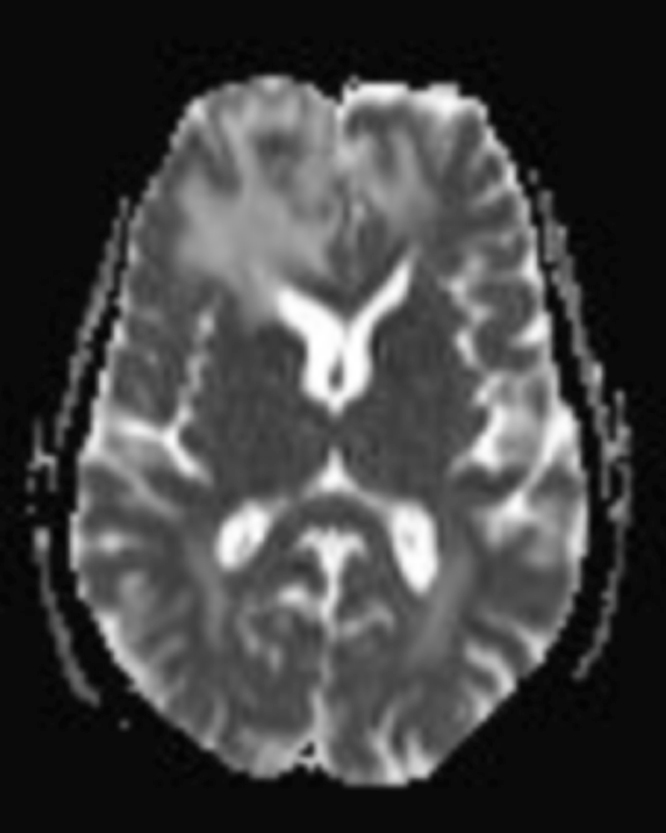

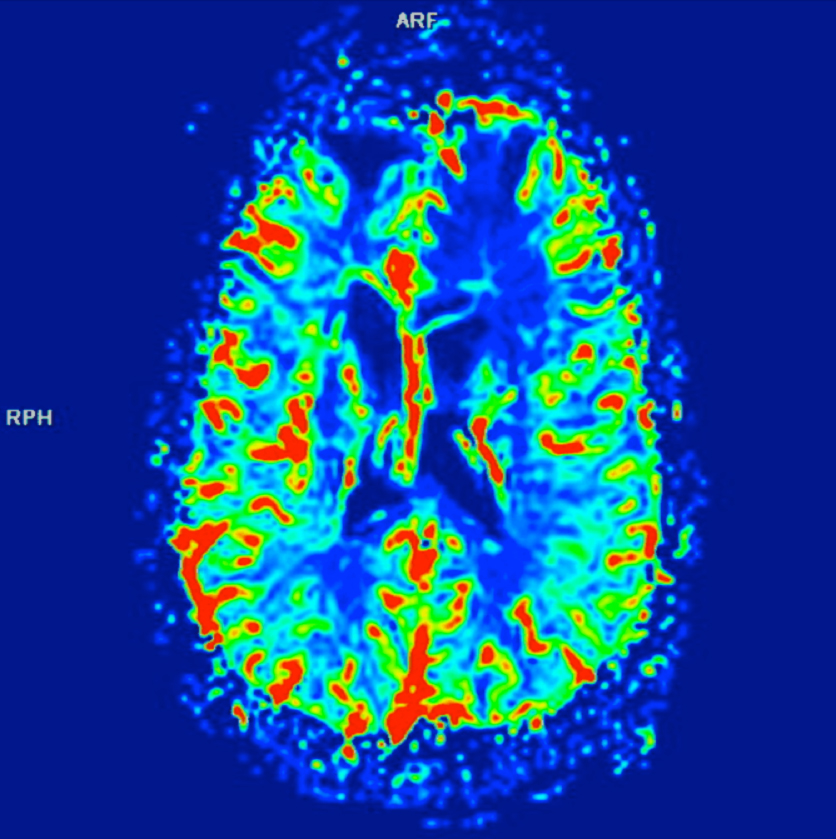

Initial axial T1 contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated a 1-cm right frontal lesion (Figure 1) consistent with brain metastasis. At 10 months post-SRS, axial T1 contrast-enhanced MRI showed punctate enhancement, suggesting excellent response to treatment (Figure 3). One month later, axial T1 contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrated interval enlargement of the enhancing area (Figure 4). At 16 months post-SRS, axial T1 contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrated an increase in the size of the treated lesion to more than twice the pretreatment area (Figure 5). Additional imaging was obtained to distinguish radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence. Advanced imaging techniques included relative cerebral blood volume MRI (rCBV) and DWI with associated ADC, which showed no decrease in diffusion (Figure 5). Metabolic imaging with FDG-PET demonstrated focal photopenia with decreased FDG uptake in the anterior right frontal lobe consistent with radiation changes (Figure 5).

Diagnosis

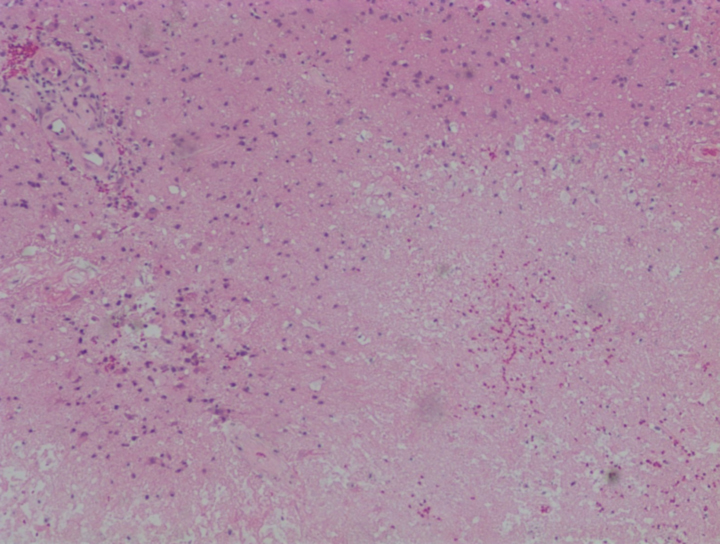

Differential diagnosis included radiation necrosis, tumor progression, or mixed radiation necrosis and tumor progression. Histopathology at the time of resection demonstrated radiation necrosis with no evidence of recurrent tumor (Figure 6).

Discussion

Each year, approximately 170,000 cancer patients develop brain metastases.1 The current paradigm for treatment of brain metastases often includes SRS, particularly for patients with 3 or fewer lesions all <4 cm, with good performance status.2 The most serious side effect of SRS is radiation necrosis. Asymptomatic radiation necrosis occurs in an unknown number of patients, but some reports suggest that up to 50% of patients demonstrate radiographic changes consistent with radiation necrosis. Clinical, or symptomatic, radiation necrosis may occur in up to 14% of patients.3 The duration and severity of symptoms associated with radiation necrosis vary from a stable, asymptomatic clinical picture of limited duration to a rapidly progressive, lethal course.

The gold standard for diagnosing radiation necrosis is histopathology. To provide an accurate, noninvasive way to distinguish radiation necrosis from tumor progression, standard series MRI scans have been evaluated using characteristic imaging findings, such as “T1/T2 mismatch,” or the ratio of the area of a discreet nodule on T2-weighted axial MRI to the area of a discreet nodule on T1 contrast-enhanced axial MRI, with mixed results.4-6

Advanced imaging techniques with DWI with ADC mapping, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), MR spectroscopy, PET with FDG and other novel radiotracers, and perfusion imaging (perfusion CT and perfusion MRI) have varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity for radiation necrosis and tumor recurrence (Table 1).6-10 Standard series MRI with perfusion imaging and metabolic imaging with PET are relatively widely available and have relatively high sensitivity and specificity for radiation necrosis and tumor progression. In a small series, multi-voxel MR spectroscopy has demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity for tumor recurrence.3-10

In our case, the patient was asymptomatic despite an enlarging mass in the context of no increase in rCBV, no decrease in ADC, and a decrease in uptake on PET—all supportive of a diagnosis of radiation necrosis. Histopathology confirmed the suspected diagnosis.

Many times, a patient’s radiologic workup will contain some series supportive of radiation necrosis while others support tumor recurrence. Physicians often obtain serial images and consider administering an empiric trial of steroids, as in our case, which may help determine whether the lesion represents radiation necrosis or tumor recurrence. This methodology requires repeated imaging without a defined endpoint.

Noninvasive, accurate diagnosis of radiation necrosis versus tumor progression is important, as the clinical course of each can differ widely. In the SRS era, a high index of suspicion for post-SRS radiation necrosis and applying appropriate advanced imaging modalities will aid practitioners in diagnosing radiation necrosis or tumor recurrence, thereby permitting selection of the most appropriate treatment.

REFERENCES

- Suh J. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the management of brain metastases. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1119-1127.

- Blonigen BJ, Steinmetz RD, Levin L, et al. Irradiated volume as a predictor of brain radionecrosis after linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgery. Int. J. Radiation Oncology Biol. Phys. 2010;77:996-1001.

- Dequesada IM, Quisling RG, Yachnis A, Friedman WA. Can standard magnetic resonance imaging reliably distinguish recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis after radiosurgery for brain metastases? A radiographic-pathological study. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:898-903.

- Kano H, Kondziolka D, Lobato-Polo J, et al. T1/T2 matching to differentiate tumor growth from radiation effects after stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:486-491.

- Stockham AL, Tievsky AL, Koyfman SA, et al. Conventional MRI does not reliably distinguish radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence after stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2012;109;149-158.

- Chernov M, Hayashi M, Izawa M, et al. Differentiation of the radiation-induced necrosis and tumor recurrence after Gamma Knife radiosurgery for brain metastases: Importance of multi-voxel proton MRS. Minim Invas Neurosurg. 2005;48:228-234.

- Chao ST,Suh JH,Raja S,et al. The sensitivity and specificity of FDGPETin distinguishing current brain tumor from radionecrosis in patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Cancer.2001;96:191-197.

- BarajasRF, Chang JS, Sneed PK, et al. Distinguishing recurrent intra-axial metastatic tumor from radiation necrosis following gamma knife radiosurgery using dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30: 367-372.

- Vidiri A, Guerrisi A, Pinzi V, et al. Perfusion computed tomography (PCT) adopting different perfusion metrics: Recurrence of brain metastasis or radiation necrosis? Eur J Radiol.2012;81:1246-1252.

- Matsunaga S, Shuto T, Takase H, et al. Semiquantitative analysis using thallium-201SPECTfor differential diagnosis between tumor recurrence and radiation necrosis after Gamma Knife surgery for malignant brain tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;Apr 27. [Epub ahead of print].