Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for lung cancer

Images

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has evolved over the past 15 years and revolutionized the management of early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Compared to conventional radiation therapy, SBRT offers superior outcomes, lower costs and greater patient convenience.1 SBRT likewise offers local control and cancer outcomes approaching surgical resection2-8 with lower risk of treatment-related morbidity, making SBRT the treatment of choice for medically inoperable and many high-risk surgical candidates. Encouraging results in this population have led to the investigation of SBRT’s role in operable stage I NSCLC, lung oligometastasis, stage I small cell lung cancer, and potentially as a boost to conventional radiation therapy for locally advanced NSCLC. The lessons learned in the lung SBRT experience also serve as a model for developing SBRT in other mobile soft-tissue sites, including the liver, pancreas, adrenal gland and prostate.

Technique

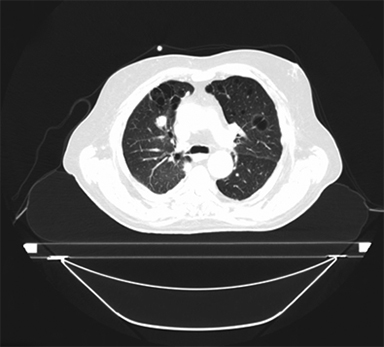

SBRT treatment planning begins with careful immobilization of the target with motion limited to <5-10 mm. This may be accomplished by abdominal compression (Figure 1), respiratory gating using either controlled breath-hold or external surrogates, or tumor tracking/respiratory modeling. Immobilization should be assessed by either fluoroscopy or 4DCT imaging at simulation, and verified by cone-beam CT (CBCT) or other imaging during treatment.

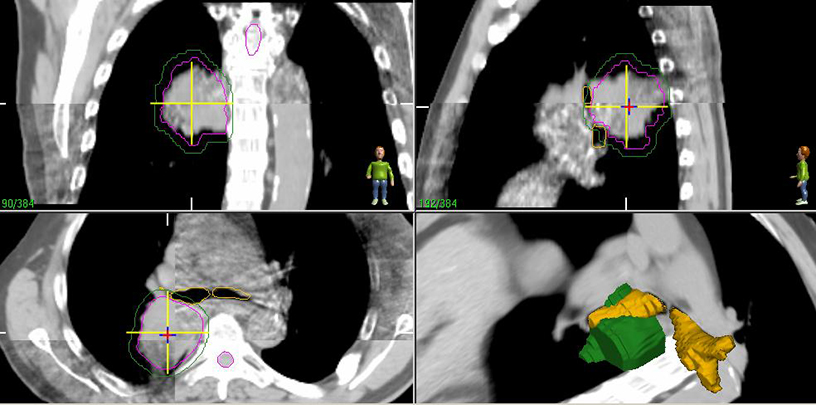

Historically, the planning target volume (PTV) was created from a fixed expansion (1 cm superior-inferior, 5 mm axially) of the contoured gross tumor volume (GTV),7 although this can alternatively be derived from the union of multi-phasic CT GTV’s (free-breathing, inhale, exhale) or 4DCT images into an internal target volume (ITV), which is then expanded uniformly by 5 mm yielding the PTV. Expanding the 4DCT ITV typically results in a smaller PTV, and likely more consistently represents the actual tumor motion, as well as center of mass.9

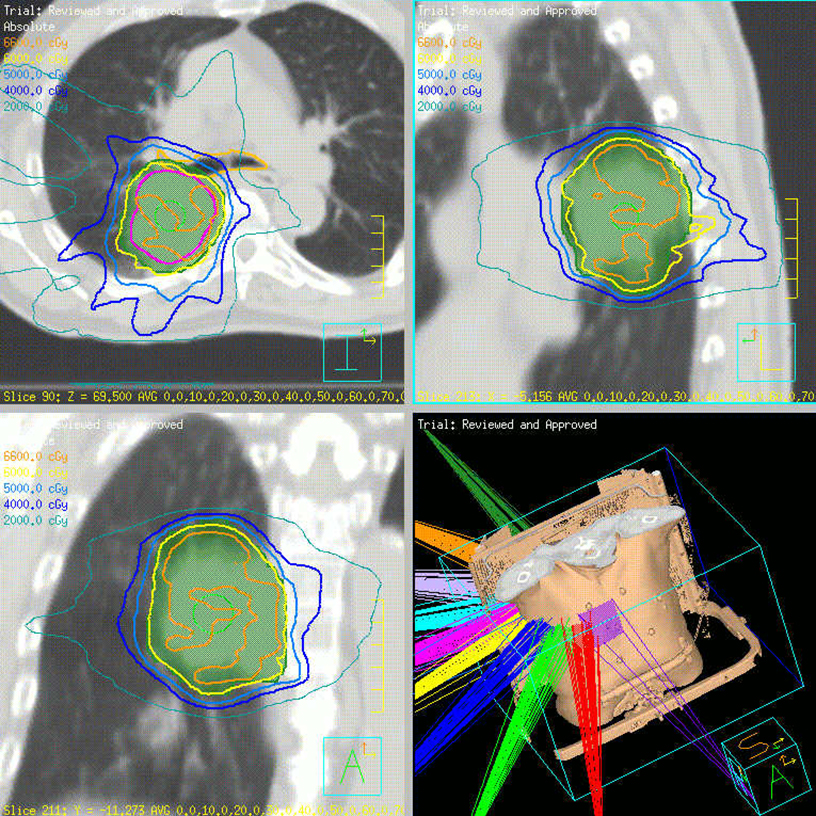

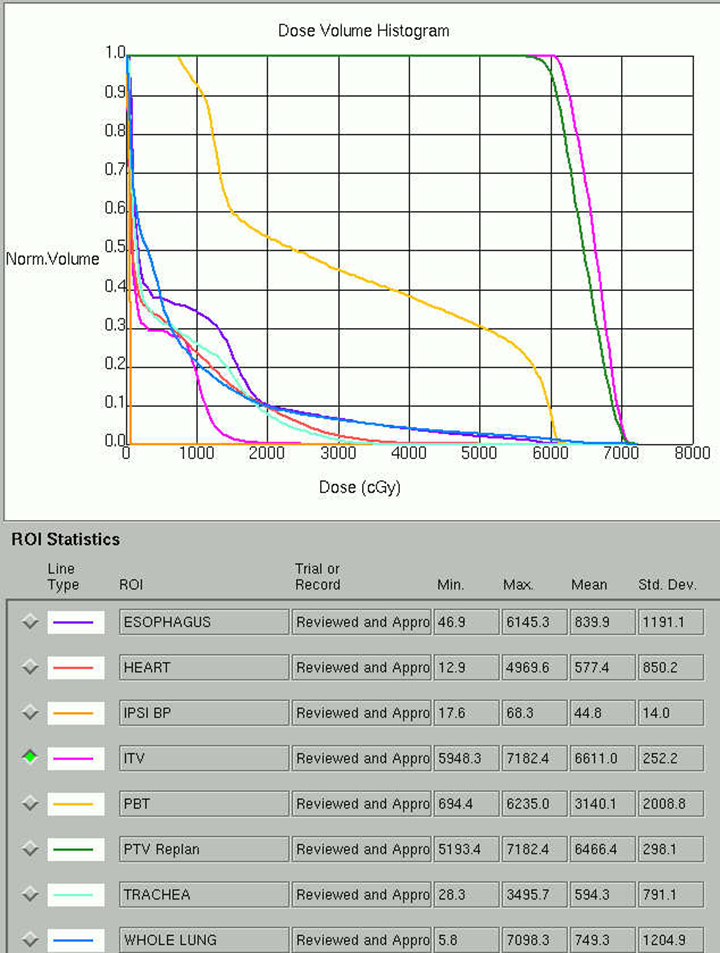

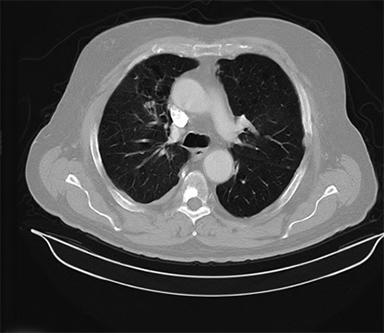

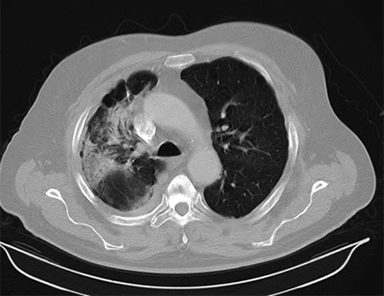

Beam arrangement may consist of 6 or more non-coplanar open beams, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) beams, non-coplanar volumetric arcs (typically at least 3 arcs, each offset by 30-40 degrees), intensity-modulated arc therapy, or alternatively, particle-based therapy.10,11 The use of IMRT in treating small moving lung targets is controversial due to concerns of potential underdosing, although IMRT is allowed by recent protocols such as RTOG 0813,10 and reported outcomes with IMRT have been on par with other techniques.12 Planning should utilize collapsed cone convolution or Monte Carlo algorithms, as there is a suggestion that pencil-beam algorithms may compromise tumor control due to more variable under-dosing.13 Our institution uses the 4D-derived average CT as the planning image for the best estimate of density and tumor center-of-mass. Planning should focus on maximizing conformality and rapid dose fall-off. Heterogeneity is acceptable and may be desirable for purposes of faster fall-off, provided critical serial structures are not overexposed (Figures 2 and 3). Constraints should be based on appropriate protocols for the target being treated, such as RTOG 0236, 0813, 0915, or large institutional experiences.

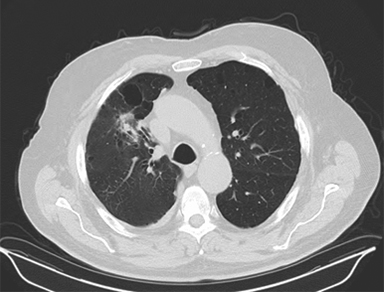

Image guidance during treatment initially consisted of bony registration followed by port films, although modern approaches typically rely on CBCT (Figure 4). Free-breathing CT may not represent the true tumor center-of-mass due to respiratory motion, and a pitfall can be created by matching free breathing CT to a CBCT tumor at the time of treatment, potentially introducing a systematic error that occasionally exceeds the PTV expansion.9 One should either use the average CT as the reference for matching, or otherwise localize only to bony anatomy if using a free-breathing image while verifying that the CBCT tumor falls within the ITV.

Patients should be routinely reimaged with CT after treatment for response assessment realizing that significant fibrotic reactions may occur (Figure 5).14 Concerning features on CT include an enlarging mass-like density, as well as enlargement in the superior-inferior axis.15 We typically reserve positron emission tomography (PET) scans for evaluating whether a lesion which appears suspicious on CT is recurrence vs. fibrosis. While no absolute standardized uptake value (SUV) cut-off exists, recurrence has been associated with SUV increases as well as residual SUV > 5 after SBRT.15 Enlarging hypermetabolic lesions should undergo biopsy as there are occasional cases where high residual metabolism may be due to inflammation rather than recurrence.16

Cancer outcomes after SBRT for stage I NSCLC

Tumor control

Local control (LC) of the index lesion after lung SBRT is typically defined as the absence of tumor progression within 1 cm of the primary tumor site,7 and has historically ranged from 90-98%,2-8 consistent with a prospective surgical series showing an LRF rate of 5-7% for lobectomy, and 8-17% for sublobar resection.17,18 Of note when comparing to surgical series, the terms lobar control (absence of failure within the treated lobe), and loco-regional control (LRC, absence of local, lobar, or nodal recurrence) become relevant. RTOG 0236, a landmark prospective trial of SBRT using 60 Gy in 3 fractions (estimated 54 Gy in 3 fractions with heterogeneity corrections) for peripheral stage I NSCLC, demonstrated 3-year LC of 97.6%, lobar control of 90.6%, LRC of 87.2%, and a 22.1% rate of distant recurrence7, consistent with other series.2-8 Due in large part to the comorbidities of medically inoperable patients receiving SBRT, overall survival (OS) is typically lower in surgical series (48.3% at 3 years on RTOG 0236 for instance7), while cancer-specific survival is comparable.

There are no reported randomized trials comparing the outcomes of SBRT to surgical resection, and initial attempts have closed due to poor accrual, potentially reflecting differences between perceptions of the 2 treatments. Comparing outcomes in non-randomized series suffers from selection bias, and attempts at matched-pair or propensity-adjusted analysis are still likely influenced by SBRT series including older patients with more significant comorbidities, lower performance status, and lower pulmonary function than surgical series.18 A matched-pair analysis between SBRT and wedge resection suggested improved LC with SBRT (96% vs. 80%), equivalent cause-specific survival, but better OS with surgery, attributed to differences in comorbidity.20 Comparing lobectomy to SBRT, Robinson et al. found similar LC (98.7% v. 95.3%, p=0.088), regional control, and distant control with improved lobar control and survival in surgical patients,21 with survival again perhaps related to selection. An earlier series from the same institution suggested improved local control and survival with surgical resection; however, after propensity matching, patient outcomes—including OS—came together.19 Small series from Japan and the Netherlands reporting on SBRT for potentially operable patients also show LC and OS outcomes in line with surgical series.4,5 A pooled meta-analysis of 40 SBRT studies totaling 4,850 patients and 23 surgical studies (lobar or sublobar resection, 7,071 patients total) likewise suggests no significant differences in LC between surgery and SBRT, and no effect of the percentage of potentially operable patients within SBRT series on LC.8 The meta-analysis suggests better OS in a surgical series; however, within SBRT series, mean OS was correlated with reported percent operable patients, and a regression model using age and percent operability showed no significant OS differences between SBRT and surgery after correction.

Toxicity

SBRT is well-tolerated even in the medically inoperable population. Patients may experience fatigue for 4-6 weeks following treatment.22 Pulmonary function is well-conserved22-25 with generally <3% risk of radiation pneumonitis,2-7,22-26 and even patients with extremely compromised pulmonary function exhibiting OS outcomes at or above the mean.22,24 This suggests there is no lower limit to pulmonary function for SBRT, provided patients are medically stable. Neuropathic pain and rib fractures may occur with 10-15% of treatments of targets abutting the chest wall, although symptoms are generally modest and potentially less common than in surgical series.27-29 Skin ulcers,30 brachial plexopathy,31 and bronchial32 or esophageal fistulas33 have been reported, but are extremely uncommon, and risk is modifiable during the planning process when identified.

Patient selection: Stage I NSCLC and the spectrum of operability

While there is no uniform definition of “medically inoperable,” several surrogates and multiple predictive models of surgical morbidity are in use.34 In practice, lung cancer patients fall on a spectrum from frankly unsuitable for surgery, to those at risk for surgical complications and mortality, to those at risk for quality of life changes with surgery and, finally, to patients in good health with minimal surgical risk. The first step in patient selection is for the multidisciplinary lung cancer team to stratify operative risk by considering the following:

Medically inoperable stage I NSCLC patients should receive SBRT, and not conventional radiation.1

Low-risk operable patients should proceed with surgical resection, which is the standard of care, and shown to be cost-effective relative to SBRT in modeling studies.35,36 While early data for SBRT in operable patients is encouraging,4,5 and OS between surgery and SBRT may be much closer after correction for age and comorbidities,8,19 further data is needed before accepting SBRT as a first-line option for most operable patients.

As operative risk increases, SBRT rapidly becomes the treatment of choice. Modeling studies suggest a surgical risk threshold of between 3-4% above which the cost-effectiveness decisively swings in favor of SBRT,35 a threshold consistent with treatment stratification in our clinic as well.

Some patients below this threshold may also choose SBRT due to better preservation of pulmonary function and to avoid oxygen requirements. In addition, a patient’s advancing age (despite good health) and evolving priorities may prompt the decision of a more convenient and less invasive procedure.

Peripheral tumors

SBRT for peripheral tumors has demonstrated excellent long-term safety and efficacy as noted above. Areas of controversy include:

What degree of pre-treatment staging is required?

Historically, this has been PET-based (with brain imaging for stage IB or neurological symptoms). The development of less invasive mediastinal staging such as endobronchial ultrasound-guided sampling, and migration of healthier patients toward SBRT, has raised the question of whether more aggressive staging might improve outcomes. While 15-30% of clinical stage I NSCLC is upstaged by the finding of positive hilar nodes at surgery,21,37 nodal failure rates appear paradoxically much lower after SBRT at 3-10%.2-7 Without clear predictors of a high-risk subgroup for nodal failure,38 the role of invasive staging remains controversial.

What is the ideal SBRT dose?

Excellent local control is seen with 60 Gy in 3 fractions as per RTOG 0236, although other regimens (48 Gy/4, 50 Gy/5, and 60 Gy/5) have similar outcomes without requiring as high of a biologically equivalent dose (BED). While regimens with BED > 100 Gy10 may saturate the dose response curve at low risk of toxicity,6 perhaps some safety margin is helpful.

Simplifying treatment to single fraction regimens is also under investigation with RTOG 0915 recently suggesting similar outcomes between 48 Gy in 4 fractions and 34 Gy in 1 fraction,11 while retrospective single fraction series continue to emerge.39 The ideal fractionation for peripheral tumors remains controversial with a wide range of accepted fractionation schedules. As a result, more prospective data is needed.

Central tumors

While SBRT for peripheral stage I NSCLC has uniformly been associated with low risk, treatment of tumors within 2 cm of the trachea and proximal bronchial tree was associated with only a 50% freedom from grade 3 or higher toxicity after 60 Gy in 3 fractions in an Indiana University phase II report,40 temporarily calling into question the safety of SBRT for central lung tumors. Of note, the early Japanese experiences using more moderate regimens such as 50 Gy in 5 fractions never discriminated between central or peripheral lesions without note of excessive toxicity in any subgroup.6 Since then, additional reports of SBRT safety for central tumors have emerged using moderate dose regimens from 50-70 Gy in 4-10 fractions.41-43 RTOG 0813, a multi-institutional dose escalation study for centrally located stage I NSCLC, also recently completed accrual escalating SBRT dose from 50 to 60 Gy in 5 fractions without protocol interruption from dose-limiting toxicity.10 The early SBRT experiences employed few constraints focusing primarily on the maximization of conformality. Modern reports include a far more extensive set of normal tissue constraints, albeit still preliminary and only modestly validated. For patients presenting with larger central tumors, these constraints may not always be achievable. In this case, there is controversy over defaulting to conventionally fractionated radiation, although in my opinion, risk-adapted SBRT techniques such as the Dutch regimen of 60 Gy in 8 fractions maintain a BED > 100 Gy and are associated with excellent local control and safety.42 While there is some inherent risk with SBRT for such large targets, failure to control these lesions often also leads to local morbidity.

Additional lung SBRT applications

Stage I small cell lung cancer (SCLC)

While SCLC is typically treated with concurrent chemoradiation, rare stage I presentations have been managed with success by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. By extension, 2 recent small series have explored SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in medically inoperable and poor risk stage I SCLC.44,45 Prophylactic cranial irradiation in this setting is controversial.

Oligometastasis

SBRT may serve a role in managing lung oligometastasis with published series frequently treating up to 5 lung metastasis during SBRT, although in our practice it’s typically limited to 1-2 oligometastatic sites. When treating oligometastasis, the intent of treatment must be clearly defined and balanced against the risks and cost of therapy.46 SBRT is most likely to add value in this setting with careful patient selection and with potential indications, including:

Curative intent treatment of patients with single lesions from metastatic colon or breast primaries based on extrapolation from surgical literature.

Newly diagnosed limited metastasis—ideally solitary—with a long interval from previous therapy, in which case SBRT might offer a delay in the need for potentially more toxic systemic therapy.

Isolated progression after a long interval of control on systemic therapy, possibly sterilizing isolated drug-resistant clones, best described in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)- or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated NSCLC setting.47

Limited residual disease after a long interval of control on systemic therapy with the intent of a break from systemic therapy.

SBRT as a boost for stage III NSCLC

While OS is not compromised, local control after chemoradiation for locally advanced NSCLC has been modest compared to surgical series with further dose escalation failing to improve outcomes.48,49,33 SBRT is an alternative method of dose-intensification recently explored in 2 prospective series.50,51 Feddock et al. reported the use of an SBRT boost of either 10 Gy x 2 for peripheral targets, or 6.5 Gy x 3 for central targets (per the RTOG 0813 definition) after 60 Gy conventional chemoradiation.50 Treatment was well-tolerated (after modifications to the initial dose regimen for central tumors), and LC was a promising 83% at median 13 months. SBRT boost is a novel treatment approach with further investigation needed before widespread adoption.

Re-irradiation

Several series describe the use of SBRT for salvage of either isolated failure after conventional radiation for locally advanced disease,52-56 or SBRT for early stage disease.57-59 In both cases, patient selection is critical given modest progression-free survival and risk of toxicity. For local recurrences after prior EBRT, SBRT doses with BED > 100 Gy10 are associated with short-term LC ranging from 65-98%, although dyspnea and pneumonitis are common. Treatment of central or nodal recurrences is associated with a very high risk of toxicity.56 SBRT for local recurrence after previous SBRT of peripheral recurrences <5 cm is associated with short-term LC of 33-60% after re-irradiation, while repeat SBRT for central tumors has been associated with significant toxicity and should be approached with extreme caution.

Conclusion

SBRT is an innovative treatment approach and represents the standard of care for medically inoperable stage I NSCLC. As results mature and techniques evolve, SBRT may be expanded to progressively healthier populations, while its role in locally advanced disease, recurrent disease, SCLC and oligometatasis continues to be explored.

References

- Grutters JP, Kessels AG, Pijls-Johannesma M, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of radiotherapy with photons, protons and carbon-ions for non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2010;95:32-40.

- Fakiris AJ, McGarry RC, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung carcinoma: four-year results of a prospective phase II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:677-682.

- Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, Smit EF, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Outcomes of risk-adapted fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:685-692.

- Lagerwaard FJ, Verstegen NE, Haasbeek CJ, et al. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in patients with potentially operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:348-353.

- Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: can SBRT be comparable to surgery? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:1352-1358.

- Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (HypoFXSRT) for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: updated results of 257 patients in a Japanese multi-institutional study. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:S94-100.

- Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1070-1076.

- Zheng X, Schipper M, Kidwell K, et al. Survival Outcome After Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy and Surgery for Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;S0360-3016(14)00706-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.055. [Epub ahead of print].

- Wang L, Hayes S, Paskalev K, et al. Dosimetric comparison of stereotactic body radiotherapy using 4D CT and multiphase CT images for treatment planning of lung cancer: evaluation of the impact on daily dose coverage. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:314-324.

- RTOG 0813. (Accessed 07/25/14, at http://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0813.)

- RTOG 0915. at http://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0915.)

- Videtic GM, Stephans K, Reddy C, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy-based stereotactic body radiotherapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer: excellent local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:344-349.

- Latifi K, Oliver J, Baker R, et al. Study of 201 non-small cell lung cancer patients given stereotactic ablative radiation therapy shows local control dependence on dose calculation algorithm. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1108-1113.

- Bradley J. Radiographic response and clinical toxicity following SBRT for stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:S118-124.

- Huang K, Dahele M, Senan S, et al. Radiographic changes after lung stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR)—can we distinguish recurrence from fibrosis? A systematic review of the literature. Radiother Oncol: J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2012;102:335-342.

- Henderson MA, Hoopes DJ, Fletcher JW, et al. A pilot trial of serial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with medically inoperable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer treated with hypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:789-795.

- Fernando HC, Landreneau RJ, Mandrekar SJ, et al. Impact of brachytherapy on local recurrence rates after sublobar resection: results from ACOSOG Z4032 (Alliance), a phase III randomized trial for high-risk operable non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. June 30, 2014, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4115. [Epub ahead of print].

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:615-622; discussion 22-3.

- Crabtree TD, Denlinger CE, Meyers BF, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus surgical resection for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:377-386.

- Grills IS, Mangona VS, Welsh R, et al. Outcomes after stereotactic lung radiotherapy or wedge resection for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:928-935.

- Robinson CG, DeWees TA, El Naqa IM, et al. Patterns of failure after stereotactic body radiation therapy or lobar resection for clinical stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:192-201.

- Videtic GM, Reddy CA, Sorenson L. A prospective study of quality of life including fatigue and pulmonary function after stereotactic body radiotherapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:211-218.

- Henderson M, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Baseline pulmonary function as a predictor for survival and decline in pulmonary function over time in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for the treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:404-409.

- Stanic S, Paulus R, Timmerman RD, et al. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1092-1099.

- Stephans KL, Djemil T, Reddy CA, et al. Comprehensive analysis of pulmonary function Test (PFT) changes after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I lung cancer in medically inoperable patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:838-844.

- Palma D, Lagerwaard F, Rodrigues G, Haasbeek C, Senan S. Curative treatment of Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer in patients with severe COPD: stereotactic radiotherapy outcomes and systematic review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1149-1156.

- Dunlap NE, Cai J, Biedermann GB, et al. Chest wall volume receiving >30 Gy predicts risk of severe pain and/or rib fracture after lung stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:796-801.

- Stephans KL, Djemil T, Tendulkar RD, Robinson CG, Reddy CA, Videtic GM. Prediction of chest wall toxicity from lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:974-980.

- Voroney JP, Hope A, Dahele MR, et al. Chest wall pain and rib fracture after stereotactic radiotherapy for peripheral non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1035-1037.

- Hoppe BS, Laser B, Kowalski AV, et al. Acute skin toxicity following stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: who’s at risk? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1283-1286.

- Forquer JA, Fakiris AJ, Timmerman RD, et al. Brachial plexopathy from stereotactic body radiotherapy in early-stage NSCLC: dose-limiting toxicity in apical tumor sites. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:408-413.

- Corradetti MN, Haas AR, Rengan R. Central-airway necrosis after stereotactic body-radiation therapy. New Eng J Med. 2012;366:2327-2329.

- Stephans KL, Djemil T, Diaconu C, et al. Esophageal Dose Tolerance to Hypofractionated Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy: Risk Factors for Late Toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014 Jul 8. pii: S0360-3016(14)00596-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.011. [Epub ahead of print].

- Donington J, Ferguson M, Mazzone P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians and Society of Thoracic Surgeons consensus statement for evaluation and management for high-risk patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2012;142:1620-1635.

- Louie AV, Rodrigues G, Hannouf M, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy versus surgery for medically operable Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a Markov model-based decision analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:964-973.

- Puri V, Crabtree TD, Kymes S, et al. A comparison of surgical intervention and stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I lung cancer in high-risk patients: a decision analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:428-436.

- Sagawa M, Saitoh Y, Takahashi S, et al. Analysis of patients with resected small-size (less than or equal to 2 cm in diameter) peripheral type lung cancer lesions. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;28:944-949.

- Marwaha G, Reddy C, Stephans K, Videtic G. Lung SBRT: Regional nodal failure is not predicted by tumor size. J Thorac oncol. 2014;In Press.

- Videtic GM, Stephans KL, Woody NM, et al. 30 Gy or 34 Gy? Comparing 2 single-fraction SBRT dose schedules for stage I medically inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014 Jul 8. pii: S0360-3016(14)00615-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.017. [Epub ahead of print].

- Timmerman R, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4833-4839.

- Chang JY, Li QQ, Xu QY, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for centrally located early stage or isolated parenchymal recurrences of non-small cell lung cancer: how to fly in a “no fly zone.” Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1120-1128.

- Haasbeek CJ, Lagerwaard FJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for centrally located early-stage lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:2036-2043.

- Rowe BP, Boffa DJ, Wilson LD, Kim AW, Detterbeck FC, Decker RH. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for central lung tumors. J Thorac Oncol. Cancer 2012;7:1394-1399.

- Shioyama Y, Nakamura K, Sasaki T, et al. Clinical results of stereotactic body radiotherapy for Stage I small-cell lung cancer: a single institutional experience. J Radiat Res. 2013;54:108-112.

- Videtic GM, Stephans KL, Woody NM, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy-based treatment model for stage I medically inoperable small cell lung cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2013;3:301-306.

- Ashworth AB, Senan S, Palma DA, et al. An individual patient data metaanalysis of outcomes and prognostic factors after treatment of oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014. Published Online: May 15, 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2014.04.003.

- Gan GN, Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, et al. Stereotactic radiation therapy can safely and durably control sites of extra-central nervous system oligoprogressive disease in anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive lung cancer patients receiving crizotinib. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:892-898.

- Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:379-386.

- Machtay M, Paulus R, Moughan J, et al. Defining local-regional control and its importance in locally advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:716-22.

- Feddock J, Arnold SM, Shelton BJ, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy can be used safely to boost residual disease in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:1325-1331.

- Karam SD, Horne ZD, Hong RL, McRae D, Duhamel D, Nasr NM. Dose escalation with stereotactic body radiation therapy boost for locally advanced non small cell lung cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:179.

- Liu H, Zhang X, Vinogradskiy YY, Swisher SG, Komaki R, Chang JY. Predicting radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic ablative radiation therapy in patients previously treated with conventional thoracic radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1017-1023.

- Parks J, Kloecker G, Woo S, Dunlap NE. Stereotactic body radiation therapy as salvage for intrathoracic recurrence in patients with previously irradiated locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014, Jan 22. [Epub ahead of print].

- Reyngold M, Wu AJ, McLane A, et al. Toxicity and outcomes of thoracic re-irradiation using stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:99.

- Trakul N, Harris JP, Le QT, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for reirradiation of locally recurrent lung tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1462-1465.

- Trovo M, Minatel E, Durofil E, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for re-irradiation of persistent or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1114-1119.

- Hearn JW, Videtic GM, Djemil T, Stephans KL. Salvage stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for local failure after primary lung SBRT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014 Jul 10. pii: S0360-3016(14)00699-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.048. [Epub ahead of print].

- Peulen H, Karlsson K, Lindberg K, et al. Toxicity after reirradiation of pulmonary tumours with stereotactic body radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:260-266.

- Valakh V, Miyamoto C, Micaily B, et al. Repeat stereotactic body radiation therapy for patients with pulmonary malignancies who had previously received SBRT to the same or an adjacent tumor site. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:680-685.