Personality Mapping and Emotional Intelligence Education in Radiation Oncology

Affiliations

- 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Health System, Miami, FL

- 2 University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL

- 3 Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology/Gastroenterology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

- 4 Department of Surgery, Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX

- 5 Department of Radiation Oncology, SPEROS Medical Director, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

- 6 Department of Radiation Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

Objectives:

Emotional intelligence is essential for effective interprofessional collaboration, particularly in complex clinical settings like radiation oncology. Personality reflection tools may enhance team communication and social awareness. This study explored the distribution of personality profiles across professional roles within a radiation oncology department using the True Colors framework as part of an educational initiative.

Methods:

A department-wide voluntary survey using the True Colors assessment was distributed to all staff. Participants self-identified their primary and secondary personality colors. A total of 152 responses were received from attendings (n = 14), residents (n = 14), nurses (n = 22), advanced practice providers (APPs) (n = 5), physicists (n = 15), therapists (n = 36), dosimetrists (n = 12), scheduling coordinators (n = 11), research coordinators (n = 11), research assistants (n = 2), social workers (n = 2), and administrators (n = 8). Aggregated results were presented at a town hall focused on interpersonal dynamics.

Results:

Gold was the most common primary color in patient-facing roles such as nurses, attendings, and scheduling coordinators. Green was more frequently identified by physicists, APPs, and research staff. These trends were used to initiate discussions on communication preferences and emotional intelligence. Results were integrated into the residency leadership curriculum.

Conclusions:

While the True Colors framework is not a validated psychometric instrument, its use as a reflective tool may help promote social awareness and team understanding in cancer education environments. These preliminary findings suggest a potential role for personality mapping in supporting emotional intelligence-based leadership training.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, professional development, teaming, personality mapping, true colors, interprofessional communication, radiation oncology resident leadership training, leadership education, relationship management

Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) has become a central pillar in leadership training and medical education, particularly in high-stakes environments such as oncology.1 - 3 The ability to recognize, understand, and manage one’s own emotions, as well as those of others, supports more effective communication, collaboration, and leadership in interprofessional teams.4, 5 These skills are particularly vital in radiation oncology, where successful care delivery requires tight coordination across multiple disciplines, including physicians, therapists, physicists, advanced practice providers (APPs), and administrative staff.6, 7 Indeed, in such complex multidisciplinary work environments, conflicts are anticipated and need to be effectively resolved to mitigate negative impacts such as the generation of medical errors, increased stress leading to burnout, and staff turnover. Central to many conflict scenarios is the fast pace of change in health care, which can increase workplace tension, frustration, and loss of engagement.8 Yet, few professional training programs incorporate skill development focusing on the four quadrants of the EI model, which could help to bridge this gap ( Table 1 ).9

Core competencies forming the Emotional and Social Competence Inventory

| SELF | OTHER | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | Social awareness |  |

| Emotional self-awareness | Empathy, organizational awareness | |

| Self-management | Relationship management | |

| Achievement orientation, adaptability, emotional self-control, and positive outlook | Coach and mentor, inspirational leadership, influence, conflict management, and teamwork |

Educational strategies aimed at developing EI often include activities designed to promote self-awareness and social awareness, 2 core competencies in the EI framework.10 One such strategy is the use of personality reflection tools, which are employed in many professional settings to catalyze discussions about interpersonal differences. Instruments such as the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator, DISC, and True Colors (TCs) have been used in both corporate and academic settings to prompt reflection on communication styles and behavioral tendencies.11 - 13 In addition, there is the tool known as the Thomas Kilmann Instrument,14 which measures baseline conflict management styles. Studies have shown a significant positive correlation between residents’ collaborating scores and the faculty Accrediation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency evaluations of medical knowledge, communication skills, problem-based learning, system-based practice, and professionalism.15 Interprofessional conflict is highly prevalent in clinical settings; a survey of physicians from 24 countries found that 71% reported conflicts occur frequently, and more than 80% described these conflicts as harmful.16 While such conflicts can negatively impact team dynamics, they also create opportunities to improve patient care by prompting reflection on treatment and management approaches. In this context, the TC assessment provides a practical tool to increase self-awareness and help individuals recognize differences in communication and decision-making that can enhance teamwork, collaboration, and ultimately patient outcomes.

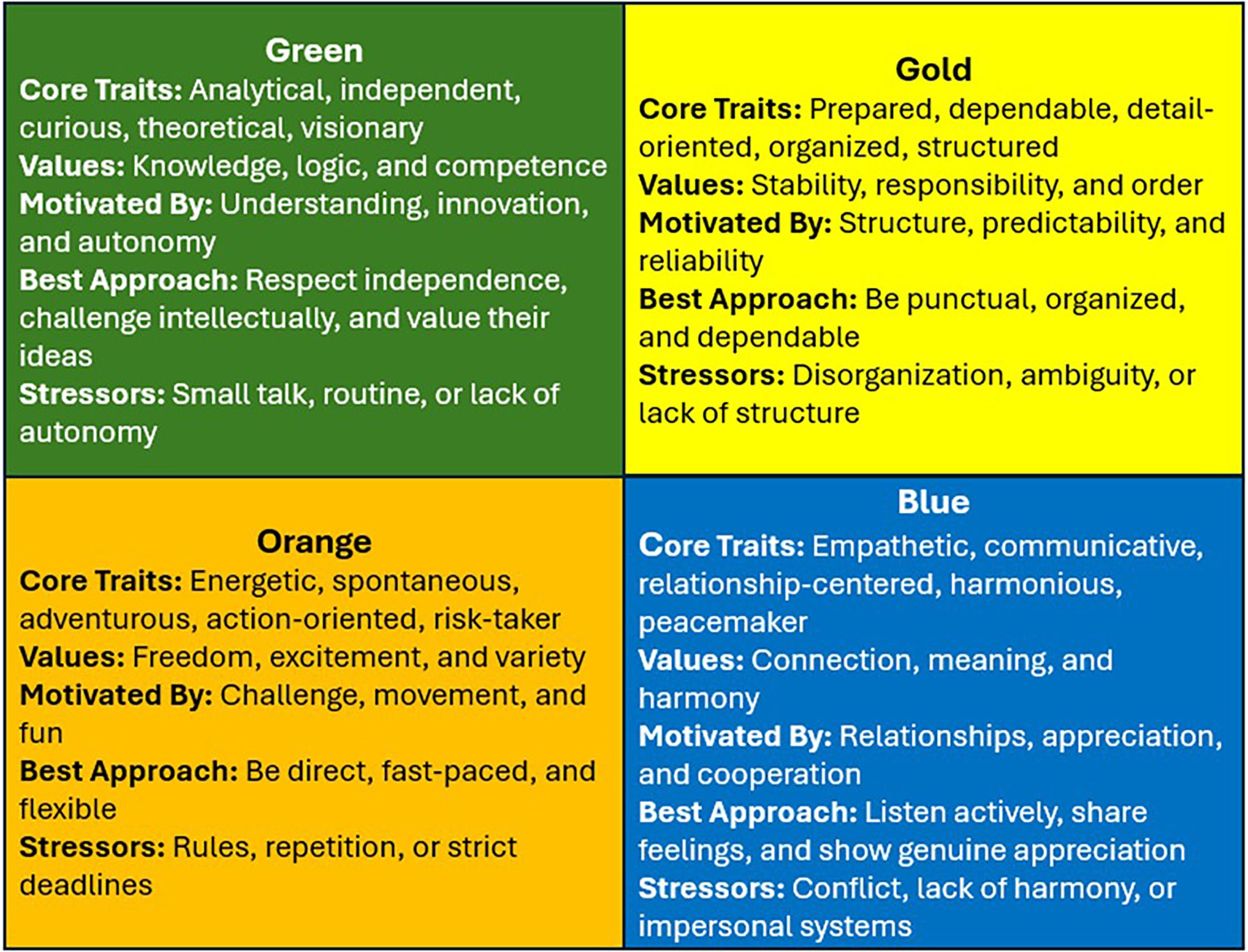

While personality assessments of this kind are not supported by strong psychometric validation,17 they may still hold educational value when used to support introspection and dialog. The TC system categorizes individuals into four temperament groups—Gold, Green, Blue, and Orange—each representing a primary interpersonal orientation ( Figure 1 ). In this model, Gold individuals, structured and dependable; Green individuals, analytical and independent; Blue individuals, empathetic and communicative; and Orange individuals, spontaneous and adaptable.

Summary of the True Colors personality framework illustrating four primary personality types (Blue, Gold, Orange, and Green), each defined by distinct core traits, values, motivators, and stressors. The framework highlights how individual differences shape communication, decision-making, and collaboration styles.

In our department, we sought to use the TC framework not as a diagnostic tool, but as a conversational springboard for promoting social awareness. This project was integrated into an EI-based leadership development curriculum for residents and designed to support broader interprofessional engagement. While the results are not intended to be generalizable, we hypothesized that they would provide insight into personality diversity within an academic cancer center and serve as a starting point for team-based educational discussions.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This descriptive analysis was an institutional review board (IRB)-exempt educational quality improvement initiative conducted in the Department of Radiation Oncology at our NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. The primary aim was to map interpersonal style diversity within the department using the TC personality framework as a foundation for leadership and communication-based education.

Survey Development and Distribution

The TC personality assessment was used to classify participants into one of four primary personality types based on value-driven behavioral preferences. These were represented with the colors Gold, Green, Blue, and Orange ( Figure 1 ). This test was developed over 40 years ago to reliably predict individual profiles. The TC Assessment test ( www.truecolorsintl.com/personality-assessment ) has since been conducted on 10,000 participants to ensure data reliability, construct validity, and disparate impact as certified by the Assessment Standards Institute.

In order to maximize representation of each interprofessional group within the radiation oncology department, the first author scheduled presentations to describe the TC survey at each section’s regular meetings to encourage participation. A PowerPoint presentation was developed explaining the background of each color and how this information could be used to improve working relationships. In addition, the survey was mentioned each month at department-wide faculty meetings. The survey was electronically distributed by our Patient Experience Optimization Team. Participants received their individual results and were encouraged to reflect on their interpersonal style. The study team received aggregate data by interprofessional group. No identifying or outcome-related information was collected. The survey was active for 3 months to ensure adequate time for participation.

Ethical Considerations

The project was reviewed and deemed exempt by the IRB as a nonhuman subject quality improvement activity. Participants were informed that all responses were anonymous and would be used solely for educational purposes.

Results

Participants and Color Assignment

A total of 152 individuals completed the personality assessment. Respondents represented a broad range of roles within the department, including 14 attending physicians (n = 14/25, 56%), 14 radiation oncology residents (n = 14/14, 100%), 22 nurses (n = 22/26, 84.6%), 5 APPs (n = 5/12, 41.6%), 15 physicists (n = 15/28, 53.5%), 36 radiation therapists (n = 36/60, 60%), 12 dosimetrists (n = 12/20, 60%), 11 scheduling coordinators (n = 12/12, 91.6%), 11 research coordinators (n = 11/11, 100%), 2 research assistants (n = 2/2, 100%), 2 social workers (n = 2/2, 100%), and 8 administrative staff (n = 8/10, 80%). Primary and secondary colors were assigned if that color category received the most and second-most points on the assessment, respectively. Due to this, it is possible for a participant to have multiple primary and secondary colors in the case of point ties.

Overall Color Distribution

Among the 152 participants who completed the personality assessment, the most frequently reported primary color was Gold (n = 52), followed by Green (n = 45), Blue (n = 37), and Orange (n = 28). For secondary color rankings, Green (n = 47) and Blue (n = 46) were the most common, followed by Gold (n = 35) and Orange (n = 29) ( Table 2 ).

Overall distribution of primary and secondary colors among respondents

| COLOR | PRIMARY RANK n (%) |

SECONDARY Rank n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gold | 52 (32.1) | 35 (22.3) |

| Green | 45 (27.8) | 47 (29.9) |

| Blue | 37 (22.8) | 46 (29.3) |

| Orange | 28 (17.3) | 29 (18.5) |

Primary Color Distribution by Role

Role-specific analysis revealed meaningful patterns in color distribution. Gold was the dominant primary color for most roles requiring extensive patient interaction, including nurses (n = 13), scheduling coordinators (n = 5), and attending physicians (n = 6). Green was the most common primary color for physicists (n = 9), APPs (n = 2), and research assistants (n = 1). Blue was most prevalent among radiation therapists (n = 14) and residents (n = 7). Orange appeared less frequently overall but was identified as the primary color in some smaller subgroups ( Table 3 ).

Primary color frequencies by professional role

| ROLE | ORANGE (n) | GOLD (n) | BLUE (n) | GREEN (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative staff | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Advanced practice providers | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Certified medical assistants | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Clinical research coordinators | 0 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Dosimetrists | 0 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Nurses | 1 | 13 | 3 | 5 |

| Radiation oncology residents | 1 | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| Attending physicians | 0 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Physicists | 1 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Radiation therapists | 5 | 7 | 14 | 10 |

| Research assistants | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Scheduling coordinators | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

Secondary Color Distribution by Role

Secondary color patterns were more heterogeneous but still aligned with primary color tendencies. For example, individuals with Gold as a primary color often listed Green or Blue as secondary colors. Among residents, Green was the most common secondary color (n = 4), whereas Blue was more frequent among research coordinators and APPs. Orange was more frequently reported as a secondary than a primary color across nearly all roles ( Table 4 ).

Secondary color frequencies by professional role

| ROLE | ORANGE (n) | GOLD (n) | BLUE (n) | GREEN (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative staff | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Advanced practice providers | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Certified medical assistants | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Clinical research coordinators | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Dosimetrists | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Nurses | 3 | 4 | 9 | 5 |

| Radiation oncology residents | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Attending physicians | 0 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Physicists | 0 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| Radiation therapists | 3 | 9 | 14 | 9 |

| Research assistants | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Scheduling coordinators | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

The results above represent a purely descriptive analysis of the TC distribution within a large, interprofessional, single-institutional radiation oncology department. The small sample size precludes formal statistical analysis. In addition, the TC methodology lacks psychometric validation in the peer-reviewed literature, although it has been independently validated by an independent, large volume, third-party assessment.

Educational Use and Feedback

These data were presented at a departmental town hall as part of a larger educational session on EI and interpersonal communication. Each professional subgroup reviewed its own aggregate color distribution and participated in guided discussions about team dynamics, communication preferences, and leadership development. The patient experience team led the session, and although formal outcome data were not collected, qualitative feedback suggested that the exercise was well received and stimulated meaningful conversation across clinical and support teams.

One example highlighted the practical application of TC. Shortly after the TC results were distributed, there was a regularly scheduled quality improvement departmental meeting attended primarily by radiation therapists, dosimetrists, and representatives from physics. After the meeting, a conflict arose with the radiation therapists and dosimetrists, who did not feel that they had been adequately trained on the new technology that the physics group was implementing. They expressed that their concerns were minimized and devalued. When the leader heard this, he set up a subsequent meeting with the only physicist in the group who was classified as “Blue.” This physicist took the time to listen to the group’s concerns and explain how their point of view would be integrated into the new departmental process. The leader then created a new position, the physics interprofessional team coordinator, a promotion associated with a professional development role, training dosimetrists and therapists. This example aligns the physicist with the “Blue” traits, reflecting an empathetic communicative style, into a novel physics leadership position, demonstrating how awareness of personality traits can inform leadership development and professional growth.

The results were also incorporated into the radiation oncology residency leadership training curriculum with a team-based exercise whereby a medical resident and a physics resident captain both selected “teams” for an exercise involving the future structure of the anticipated proton program. Each team had a “coach” to help evaluate the questions for analysis. Each resident was asked to voluntarily disclose their TC result if comfortable, so that the captains could select balanced teams. All 14 residents did so, and then the captains were queried on how they sought to promote TC diversity on their teams and how the TC of each member would add to the team’s effectiveness. This exercise reinforced the differences between TC among colleagues and deepened the understanding of how to think through team diversity. Informal feedback after this session revealed consistently high acceptance rates among the medical and physics radiation oncology residents. This exercise was designed to foster enhanced understanding of not only TC differences but also interprofessional differences since the program consists of physics residents in addition to the medical residents in radiation oncology. The success of this pilot session will be incorporated into other leadership training activities, and formal feedback will be evaluated.

Discussion

Effective interprofessional collaboration in oncology necessitates not only clinical expertise but also the nuanced interpersonal dynamics that underpin team-based care. While the TC framework lacks formal psychometric validation, its utility in this study was not to predict performance. Rather, it served as a practical and highly feasible tool that could be implemented across a large and professionally diverse department. The initiative required minimal resources, was well-received by participants from all roles, and successfully engaged individuals from clinical, technical, and administrative backgrounds. By providing a simple, accessible vocabulary for discussing personality-driven behavior patterns, the framework established a shared language that helped bridge communication gaps and catalyze constructive discussions about collaboration and team dynamics within a highly diverse interprofessional working environment.

Strengthening these teaming skills is essential to creating safer, more cohesive health care environments. Cancer care depends on highly coordinated teams.18 In such highly complex medical environments, interpersonal conflict and burnout can directly affect patient safety by negatively influencing staff retention and work engagement.19 Burnout has been shown to contribute to poor quality of care, disengagement from work, increased medical errors, hostility toward patients, difficult relationships with co-workers, and decreased commitment to patient safety.20, 21 In a national survey of over 700 radiation therapists, 76% of medical errors were discovered by either a radiation therapist or physicist, underscoring how heavily the system relies on vigilant, high-functioning teams.22 Yet 40% of radiation therapists report that burnout and anxiety negatively affect their ability to deliver care, and 17% report experiencing workplace bullying, further heightening the risk of communication failures and team dysfunction.22

Frameworks such as TC can help address these challenges by providing a common language for understanding differences in communication styles, stress responses, and temperaments. This could reduce errors that stem from misunderstandings or assumptions and support psychological well-being among health care personnel.23, 24

The Non-Technical Skills in Medical Education Special Interest Group, a global network of clinicians, educators, and researchers, defines nontechnical skills as the combination of social and cognitive abilities that collectively support safe, effective, and efficient interprofessional care within complex health care systems.5 Their consensus emphasizes team-level competencies such as adaptability, implicit and explicit coordination, shared leadership, and conflict resolution as critical components of effective teamwork in dynamic clinical environments. By integrating these nontechnical skills with structured frameworks like TC, organizations can enhance interprofessional collaboration, mitigate burnout, and build a more resilient and reliable clinical environment.

The distribution of primary and secondary personality colors across the department revealed distinct patterns that largely aligned with professional identity. Gold was dominant in patient-facing roles, consistent with the structured, dependable, and rule-following tendencies described in the framework. Conversely, Green was more frequent in research-heavy and technical roles like physicists. These findings are intuitive but rarely discussed openly within team settings. This type of exercise brought those differences to the surface in a way that was accessible and nonjudgmental.

This study highlights the potential utility of personality mapping as a gateway to EI-based education, particularly given the increasing recognition of EI as a cornerstone of effective leadership and interprofessional collaboration in health care. The EI, especially in the domains of social awareness and relationship management, has been shown to enhance team communication and workplace culture. Foundational skills such as empathy, self-awareness, and social insight are directly linked to personal growth and leadership capacity in clinical teams.2, 25 Various models conceptualize EI as a critical competency for adaptability and professional effectiveness across medical domains.26, 27

Curricula grounded in EI have been successfully implemented in surgical training, oncology leadership programs, and interprofessional education initiatives.9, 28 What distinguishes this initiative is its inclusion of the entire department, encompassing both clinical and non-clinical staff, in a unified reflective exercise that promotes inclusivity and broad-based engagement, which are often lacking in more narrowly focused efforts. The structure of the initiative also aligns with adult learning theory, which emphasizes autonomy, relevance, and experiential engagement as essential for motivation and retention.29 Feedback from the departmental town hall indicated that participants found the activity both accurate and personally meaningful. Although this feedback is self-reported, the enthusiastic responses support the continued use of personality-based frameworks such as TC as accessible entry points into more advanced EI development.

From an implementation perspective, this initiative required minimal resources, suggesting that similar departments could replicate it with ease. The only logistical barriers were securing participation and scheduling town hall-style follow-up sessions. Importantly, faculty leadership support was critical to the normalization of the activity. In future iterations, expanding the initiative to include structured follow-up modules or conflict-resolution simulations may offer even greater utility.

A limitation of the TC instrument is that it has not undergone rigorous external validation. Indeed, the TC methodology lacks psychometric validation in the peer-reviewed literature, although it has been independently validated by an independent large-volume third-party assessment. The results above thus represent a purely descriptive analysis of the TC distribution within a large interprofessional single institutional radiation oncology department. The small sample size also precludes formal statistical analysis. In light of this, we deliberately refrained from positioning the framework as a diagnostic or predictive tool. Rather, it was employed as a reflective exercise to facilitate team-based dialog. Additionally, behavior change, communication quality, or team dynamics measurements were not included. As such, the findings should be interpreted as descriptive and exploratory, serving as a foundation for future hypothesis-driven work.

Future research might pair this type of initiative with validated tools like the Jefferson Scale of Empathy30 or the Emotional and Social Competency Inventory31 to explore whether personality reflection leads to measurable change. Alternatively, longitudinal data could assess whether individuals alter their communication approaches based on team composition awareness. Lastly, qualitative interviews could help explore how individuals internalize and respond to personality-based feedback in clinical practice.

Conclusion

This department-wide initiative used the TC framework as a reflective tool to promote EI and team awareness. Personality distributions aligned with professional roles and helped initiate discussions on communication and collaboration. The tool was incorporated into our Radiation Oncology Leadership Training course with a pilot team-based module with high informal positive feedback, suggesting a role for further training with formal evaluation. A new physics leadership role was created in direct response to the exercise, creating a novel leadership position for a faculty member whose assessment revealed his Blue TC and aligned to the departmental need for an empathetic communicator. While not a validated assessment, the tool supported educational goals and offered a practical entry point for EI training in academic oncology.