Impact of Integrated Pathologic Score on Treatment Outcomes for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer

Affiliations

- 1 Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, Bradenton, Tampa, FL

- 2 University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL

- 3 University of South Florida, Tampa, FL

- 4 H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

- 5 The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

- 6 Department of Medical Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL

- 7 Department of Surgical Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL

- 8 Department of Radiation Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL

Objective

The Integrated Pathologic Score of the College of American Pathologists (IPSCAP) grading system independently predicts overall survival (OS) in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma after non-ablative neoadjuvant therapy. This study analyzes the impact of IPSCAP on the outcomes of patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (BRPC) resected after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and 5-fraction stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Materials and Methods

This Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective study queried patients with BRPC treated between 2013 and 2023 with either neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine-abraxane and SBRT, who underwent resection. SBRT was categorized at ablative dose thresholds of ≥40 or 45 Gy. The IPSCAP score was calculated by summing tumor regression grade, pathologic tumor stage, and nodal status for patients with more than 12 lymph nodes examined and was classified into 3 groups: group 1 (score 0-3), group 2 (score 4-6), and group 3 (score 7-8). The presence of actionable somatic and germline mutations was identified. OS was defined as the time from biopsy to death or last contact (in months). Statistical analyses were performed using R software.

Results

Overall, per-unit decrease of IPSCAP was significantly associated with increased median OS (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.770, 95% CI 0.670-0.886, P < .001). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a significant difference between stratification of IPSCAP by group, with group 1 having significantly less risk of death than groups 2 and 3. Similar results were found when patients were stratified by their neoadjuvant chemotherapy: FOLFIRINOX (HR = 0.742, 95% CI 0.604-0.912, P < .01) and gemcitabine-abraxane (HR = 0.804, 95% CI 0.667-0.969, P = .022). Patients treated with ≥45 Gy were significantly more likely to have group 1 pathologic scores and had higher odds of achieving group 1 compared with those treated with <45 Gy (odds ratio, 2.458; 95% CI 1.060-5.783; P = .027, Fisher exact test).

Conclusions

This study suggests that IPSCAP incorporation is a reliable prognosticator in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and 5-fraction SBRT of OS in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma, warranting further studies with dose escalation in this population.

Keywords: stereotactic body radiation therapy, borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine-abraxane, IPSCAP, pathologic score

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains one of the most lethal malignancies, characterized by late presentation, early metastatic spread, and poor 5-year survival rates.1 Within this spectrum, borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (BRPC) defined by anatomic criteria represents a challenging subset. The contact of these tumors with nearby vasculature complicates the potential for their complete surgical resection.1, 2 Neoadjuvant therapy (NAT), including chemotherapy and radiation strategies such as conventional fractionation, hypofractionation, and ablative radiation, has been used to improve resectability and long-term outcomes.

Neoadjuvant approaches have become an increasingly accepted standard in the management of BRPC. NAT aims to downstage tumors, treat micrometastatic disease early, and increase the chances of R0 resection, ultimately offering outcomes similar to those seen in initially resectable disease.1 By initiating therapy prior to surgery, clinicians can also assess tumor biology and treatment response, which helps refine patient selection for resection.

NAT plays a critical role in improving local tumor control by reducing tumor burden and sterilizing margins near vascular structures. Multiple studies have demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) with NAT compared with upfront surgery.3, 4 Notably, concerns about increased complication rates or reduced resectability with NAT have not been substantiated, as surgical outcomes appear similar between the 2 approaches.3 As NAT usage becomes more prevalent, the need for accurate post-treatment prognostic tools has become increasingly important. Clinical staging systems like the American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) classification, which are based on untreated tumor characteristics, are less effective in predicting outcomes than the AJCC pathologic staging system, which has been validated using data from treatment-naïve patients.5, 6 In the setting of NAT, however, the optimal staging and prognostication systems remain unclear.

To address this limitation, a more dynamic prognostic system that reflects NAT response is needed. The Integrated Pathologic Score of the College of American Pathologists (IPSCAP), developed to fill this gap, was first mentioned by Sohn et al in the setting of NAT integrating nonablative radiation.6 IPSCAP is a combination staging score following NAT and subsequent resection in patients with BRPC. Pathologic tumor stage (ypT), nodal status (ypN), and histologic tumor regression grade (TRG) are added into a single composite score, with a lower IPSCAP score representing a better pathologic outcome.6 This score offers a more nuanced and informed measure of patient prognosis than traditional staging. Sohn et al reported IPSCAP outperformed AJCC pathologic staging (0, IA, IB, IIA, IIB, III, and IV) in predicting critical oncologic outcomes such as disease-free survival and OS. In addition, IPSCAP correlated with several key prognostic factors, including tumor differentiation, margin status, and recurrence risk.6 In multivariate analyses, both IPSCAP and related models (IPSMDA using the MD Anderson histopathologic response grading system) have emerged as independent predictors of survival, whereas pathologic AJCC staging alone lacks more detailed prognostic insight following NAT.6 - 8 These findings support IPSCAP’s growing role in post-treatment evaluation and its potential as a preferred tool for guiding ongoing clinical decision-making.

With the incorporation of advanced treatment modalities, such as ablative radiation therapy, including stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and hypofractionated regimens incorporating high-dose intensity-modulated radiation therapy, the addition of radiation to NAT is becoming increasingly effective at achieving local control.9, 10 Doses of 40 to 50 Gy or more (72-100 biologically equivalent dose [BED]) delivered in 5 fractions are considered within the ablative range for PDAC.11, 12 These regimens may enhance margin sterilization, particularly when paired with systemic therapy, and could further improve patient outcomes. Currently, the role of radiation as part of NAT for BRPC is controversial, and the optimal dose/fractionation strategy is unknown.13 This uncertainty has been reinforced by the negative findings of the Alliance trial, which established chemotherapy alone as an acceptable standard of care.14

By integrating key post-treatment data, IPSCAP in the setting of NAT may offer a clearer prognostication based on post-treatment tumor biology and improve adjuvant therapy patient selection. Since studies to date have not evaluated the impact of IPSCAP in NAT regimens integrating ablative radiation dosing, this study aims to further understand IPSCAP as a prognosticator of outcomes in patients with BRPC following neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus 5-fraction SBRT with subsequent resection.

Materials and Methods

An Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective study utilizing an institutional database was queried for patients with the diagnosis of BRPC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation. Eligible patients were treated with neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine-abraxane plus 5-fraction SBRT with subsequent resection between 2013 and 2023. Radiation therapy was administered in a single academic institution by gastrointestinal (GI) site-specific radiation oncologists using either conventional or MRI-guided linac. In the first 6 years of the study period, the departmental protocol consisted of delivering up to 40 Gy in 5 fractions to the gross tumor volume (GTV) after endoscopic placement of fiducial markers within the tumor, contingent on normal tissue constraints, as previously described.15 - 17 Respiratory motion techniques using abdominal compression or respiratory gating were standard, pending patient tolerance and effectiveness. In March 2019, our institution began our MRI linac program, delivering gated nonadaptive treatments for the first 4 months and then transitioning to gated adaptive technique once training proficiency was achieved.18 - 20 With MRI adaptive capability, real-time coverage of the GTV daily could be optimized while maintaining organ-at-risk (OAR) dose constraints. This was not possible with conventional linac treatment, in which daily GTV coverage was not directly assessed.

Chemotherapy cycles were determined by physician preference. Patients with full treatment and tumor characteristic data, and at least 12 nodes examined per the College of American Pathologists minimum criteria, were included.21 Patient data collected included demographics, CA19-9 marker and secretor status, chemotherapy information, radiation dosing, radiation modality, tumor pathology characteristics, germline and somatic actionable mutations, and median OS. Survival time was calculated as time from biopsy to date of death or last known contact. Actionable mutations included BRCA1, BRCA2, KRAS, ATM, PALB2, and HER2. CA-19-9 nonsecretor status was defined as < 2 u/mL pre- and post-NAT.22

IPSCAP was calculated by adding the ypT, ypN, and TRG scores to yield a value from 0 to 8. The IPSCAP score was then subclassified into 3 groups for additional analysis: group 1 (0-3), group 2 (4-6), and group 3 (7-8). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were obtained. Cox regression was performed to determine OS hazard ratios (HRs) using IPSCAP as a per-unit measurement and proportionally compared with group 1 as reference. Cox regression was again performed using group 2 as reference in order to compare group 2 and group 3. This was performed overall and stratified by neoadjuvant chemotherapy selection. Patients were also stratified by dose at or above 40 Gy and at or above 45 Gy. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox regression were performed to determine OS impact using dose threshold as a categorical measurement. Post-hoc chi-square testing (without Yates correction) and Fisher testing was performed comparing dose threshold to group 1 status. Analytics were performed using R software. Tables 1 and 2 were then created based on patient and tumor characteristics overall and stratified by IPSCAP group, respectively. Median values were utilized for reporting table statistics.

Demographic Patient Data and Characteristics of Treatment, Tumor, and Median Overall Survival

| Characteristic | n = 146 |

|---|---|

| Age | 68 (33-86) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 52.7% (77) |

| Male | 47.3% (69) |

| Radiation dose (Gy) | |

| <40 | 24% (35) |

| ≥40 | 76% (111) |

| <45 | 62.3% (91) |

| ≥45 | 37.7% (55) |

| Radiation modality and dose | |

| Conventional SBRT | 61.6% (90) |

| Adaptive MRI | 37.7% (55) |

| MRI SBRT | 0.7% (1) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Number of cycles overall | 4 (1-12) |

| FOLFIRINOX | 71 (48.6%) |

| Gemcitabine-abraxane | 75 (51.4%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Head/neck | 81.5% (119) |

| Body/tail | 18.5% (27) |

| CA19-9 | 6 N/A |

| Secretor | 93.6% (131) |

| Pre-chemo (u/mL) | 160.8 (1.2-16,600) |

| Pre-surgery (u/mL) | 27.5 (0-800.9) |

| % decrease | 78.9% (−3291.7% to 100%) |

| Non-secretor | 6.4% (9) |

| TRG | |

| Grade 0 | 2.7% (4) |

| Grade 1 | 24% (35) |

| Grade 2 | 59.6% (87) |

| Grade 3 | 13.7% (20) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 74% (108) |

| Not identified | 24% (35) |

| Unknown | 2% (3) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 47.3% (69) |

| Not identified | 45.2% (66) |

| Unknown | 7.5% (11) |

| Invasion by dose | |

| <40 Gy | |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 77.1% (27) |

| Not identified | 22.9% (8) |

| Unknown | - |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 46.8% (17) |

| Not identified | 45.7% (16) |

| Unknown | 5.7% (2) |

| ≥40 Gy | |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 73% (81) |

| Not identified | 24.3% (27) |

| Unknown | 2.7% (3) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 46.8% (52) |

| Not identified | 45% (50) |

| Unknown | 8.1% (9) |

| <45 Gy | |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 75.8% (69) |

| Not identified | 23.1% (21) |

| Unknown | 1.1% (1) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 52.7% (48) |

| Not identified | 40.7% (37) |

| Unknown | 6.6% (6) |

| ≥45 Gy | |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 70.9% (39) |

| Not identified | 25.5% (14) |

| Unknown | 3.6% (2) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 38.2% (21) |

| Not identified | 52.7% (29) |

| Unknown | 9.1% (5) |

| Overall combined survival | 33 (6-140) |

| 2-y OS | 66.4% (97) |

| 3-y OS | 45.2% (66) |

| Survival by radiation dose (Gy) | |

| <40 | 31 (13-114) |

| ≥40 | 33 (8-140) |

| <45 | 37 (6-140) |

| ≥45 | 29 (10-70) |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy; TRG, tumor regression grade.

Tumor and Treatment Characteristics Stratified by the Integrated Pathologic Score of the College of American Pathologists Group

| Characteristics (Range or Count) | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 35) | (n = 103) | (n = 8) | |

| Age | 69 (34-86) | 68 (33-81) | 70 (55-82) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 60% (21) | 50.5% (52) | 50% (4) |

| Male | 40% (14) | 49.5% (51) | 50% (4) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Head/neck | 71.4% (25) | 86.7% (89) | 62.5% (5) |

| Body/tail | 28.6% (10) | 13.6% (14) | 37.5% (3) |

| CA19-9 | 1 N/A | 4 N/A | 1 N/A |

| Secretor | 91.2% (31) | 93.9% (93) | 100% (7) |

| Pre-chemo (u/mL) | 111.1 (6.8−16600) | 176.9 (1.2−15287.1) | 288.9 (16.8-535.6) |

| Pre-surgery (u/mL) | 16 (0−342.2) | 32.5 (0-800.9) | 68.6 (25-214.8) |

| % decrease | 83.4% (−16% to 100%) | 79.4% (−3291.7% to 100%) | 60% (−122% to 91.4%) |

| Non-secretor | 8.8% (3) | 6.1% (6) | - |

| Perineural invasion | |||

| Present | 45.7% (16) | 81.5% (84) | 100% (8) |

| Not identified | 51.4% (18) | 16.5% (17) | - |

| Unknown/indeterminate | 2.9% (1) | 2% (2) | - |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||

| Present | 14.3% (5) | 55.4% (57) | 87.5% (7) |

| Not identified | 77.1% (27) | 36.9% (38) | 12.5% (1) |

| Unknown/indeterminate | 8.6% (3) | 7.7% (8) | - |

| Radiation dose 40 (% of group) | |||

| <40 Gy | 22.9% (8) | 23.3% (24) | 37.5% (3) |

| >40 Gy | 77.1% (27) | 76.7% (79) | 62.5% (5) |

| Radiation dose 40 (% of group) | |||

| <45 Gy | 45.7% (16) | 70% (69) | 75% (6) |

| >45 Gy | 54.3% (19) | 30% (34) | 25% (2) |

| Mutations (% of # tested) | |||

| Germline tested | −23 | −56 | −2 |

| Actionable mutation | 13% (3) | 19.6% (11) | − |

| No actionable mutation | 87% (20) | 80.4% (45) | 100% (2) |

| Somatic tested | −7 | −41 | −5 |

| Actionable mutation | 85.7% (6) | 70.7% (29) | 60% (3) |

| No actionable mutation | 14.3% (1) | 29.3% (12) | 40% (2) |

| Combined OS | 45 (10-136) | 30 (6-140) | 25.6 (15-65) |

| Survival by radiation dose | |||

| <40 Gy combined OS | 49 (13-88) | 29 (6-114) | 21 (21-31) |

| >40 Gy combined OS | 45 (10-136) | 30 (8-140) | 30 (15-65) |

| <45 Gy combined OS | 53.5 (10-136) | 37 (6-140) | 26 (15-65) |

| >45 Gy combined OS | 40 (18-70) | 21 (10-57) | 25 (20-30) |

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

Results

Results yielded 146 eligible patients treated according to our study parameters, with 71 (48.6%) patients treated with FOLFIRINOX and 75 (51.4%) treated with gemcitabine-abraxane. The median age in our cohort was 68, with a similar distribution in males vs females (see Table 1 ). A minority of patients achieved a complete pathologic response (2.7%), as well as a pathologic nonresponse (13.7%). The median OS for this cohort was 33 months, with a 2- and 3-year survival rate of 66.4% and 45.2%, respectively.

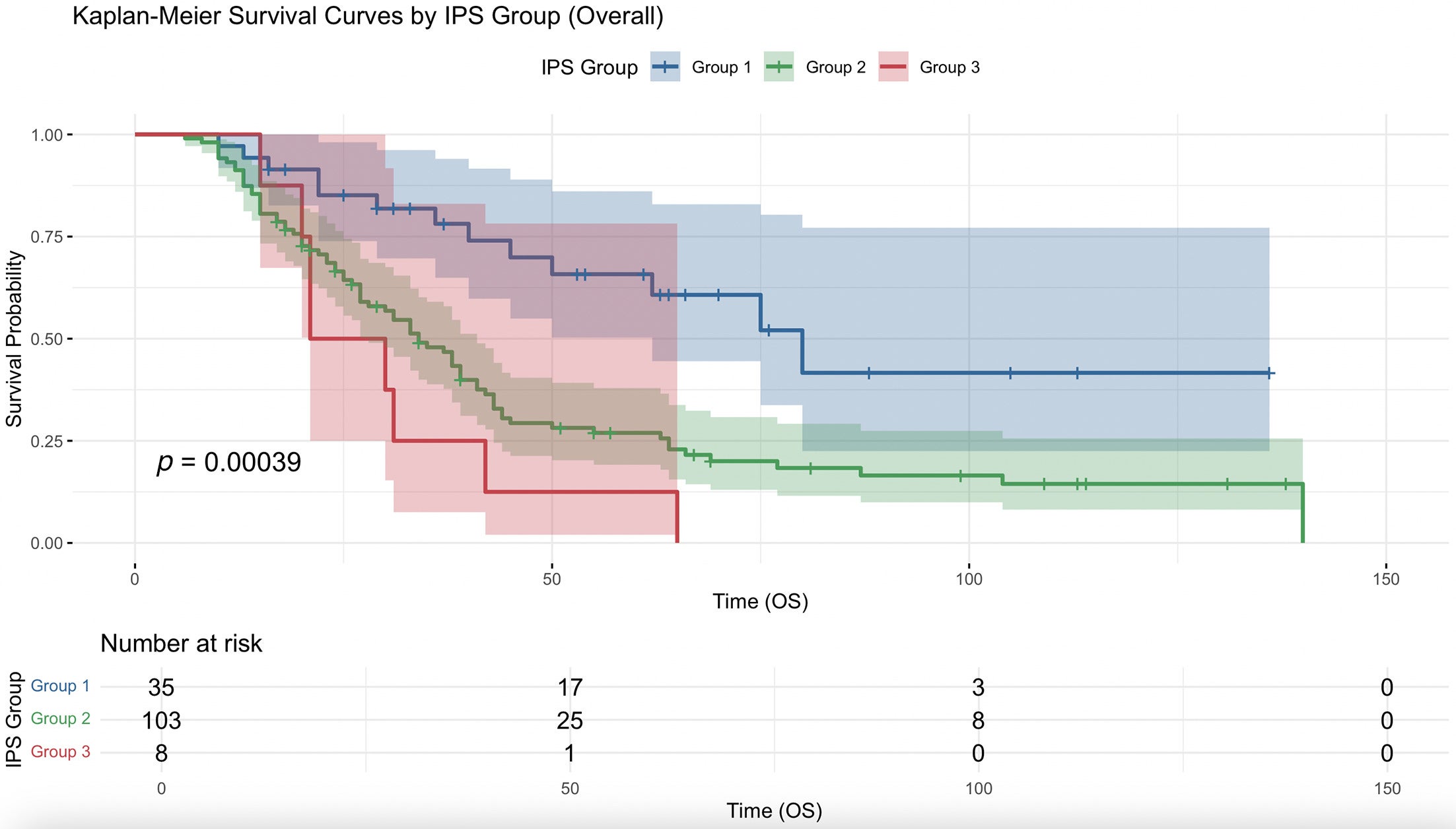

Overall, per-unit decrease of IPSCAP was significantly associated with increased median OS (HR = 0.770, 95% CI 0.670-0.886, P < .001). Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis showed a significant difference between stratification of IPSCAP by groups ( Figure 1 ). Using group 1 as reference, groups 2 and 3 had very significant increased risk of death (HR =2.718, 95% CI 1.508-4.898, P < .001) and (HR =4.654, 95% CI 1.916-11.307, P < .001), respectively. Group 3 had a higher risk of death than group 2, but it was not significant (HR = 1.713, 95% CI 0.823-3.564, P = .150).

Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing overall survival (OS) (months) between group 1 (Integrated Pathologic Score of the College of American Pathologists [IPSCAP] score 0-3), group 2 (4-6), and group 3 (7-8).

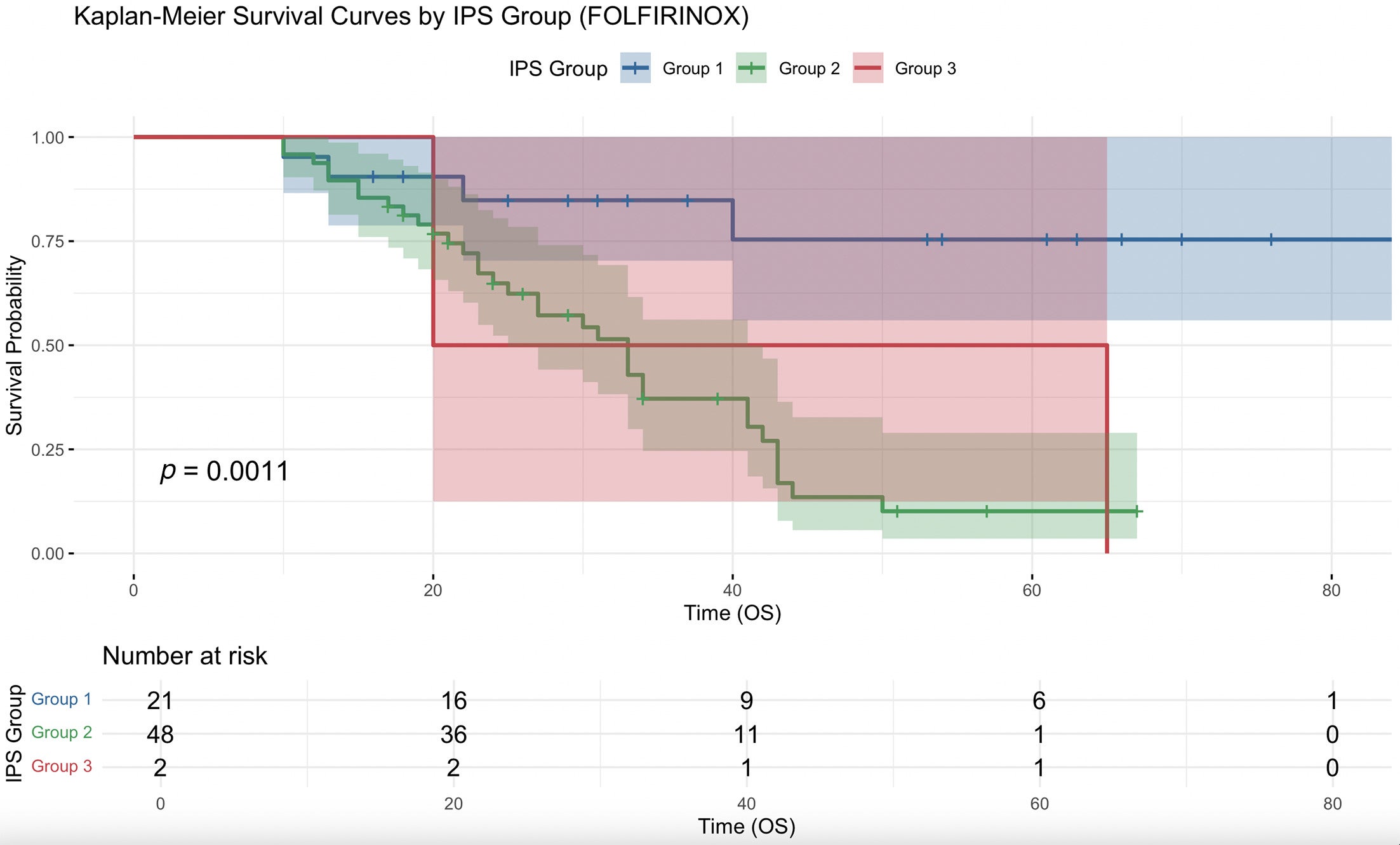

When analysis was performed only on patients receiving neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and SBRT, decreased IPSCAP was significantly associated with increased median OS (HR = 0.742, 95% CI 0.604-0.912, P < .01), with a significant survival curve ( Figure 2 ). Group 2 had a significantly higher risk of death compared with group 1 (HR = 5.883, 95% CI 2.056-16.830, P = .001) and group 3 did not (HR = 4.528, 95% CI 0.821-24.980, P = .083). Group 3 had a lower risk of death than group 2, but it was not significant (HR = 0.770, 95% CI 0.177-3.340, P = .727).

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for comparing overall survival (OS) (months) with neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and stereotactic body radiation therapy between group 1 (Integrated Pathologic Score of the College of American Pathologists [IPSCAP] score 0-3), group 2 (4-6), and group 3 (7-8).

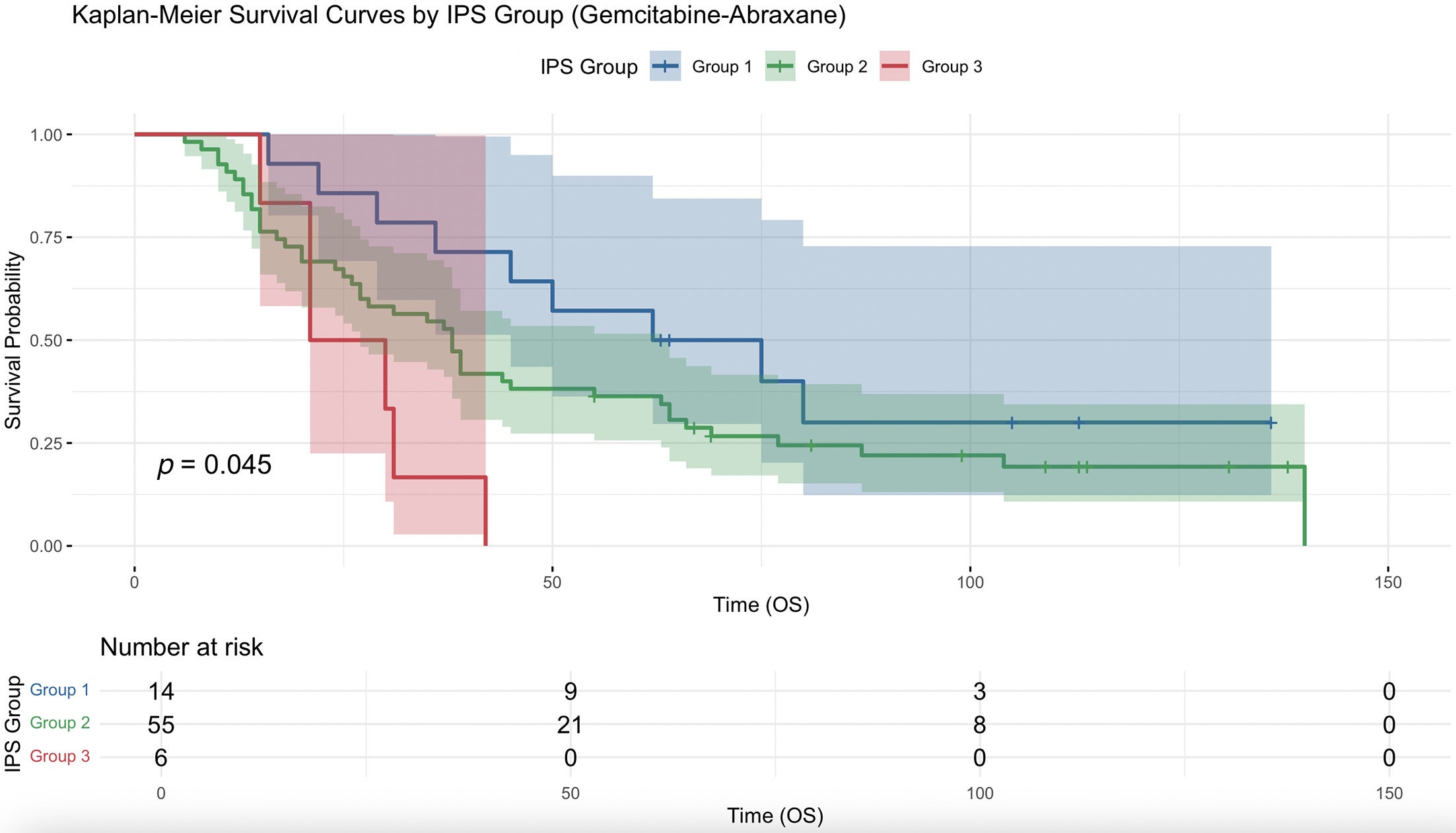

When the analysis was restricted to patients who received neoadjuvant gemcitabine-abraxane and SBRT, a lower IPSCAP score was significantly associated with increased median OS (HR = 0.804, 95% CI 0.667-0.969, P = .022) with a significant survival curve ( Figure 3 ). Patients in group 3 had a significantly higher risk of death compared with those in group 1 (HR =3.718, 95% CI 1.286-10.745, P = .015), whereas group 2 did not differ significantly from group 1 (HR = 1.654, 95% CI 0.806-3.396, P = .170). Group 3 had a higher risk than group 2, but it was not significant (HR =2.248, 95% CI 0.931-5.429, P = .072).

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for comparing overall survival (OS) (months) with neoadjuvant gemcitabine-abraxane and stereotactic body radiation therapy between group 1 (Integrated Pathologic Score of the College of American Pathologists [IPSCAP] score 0-3), group 2 (4-6), and group 3 (7-8).

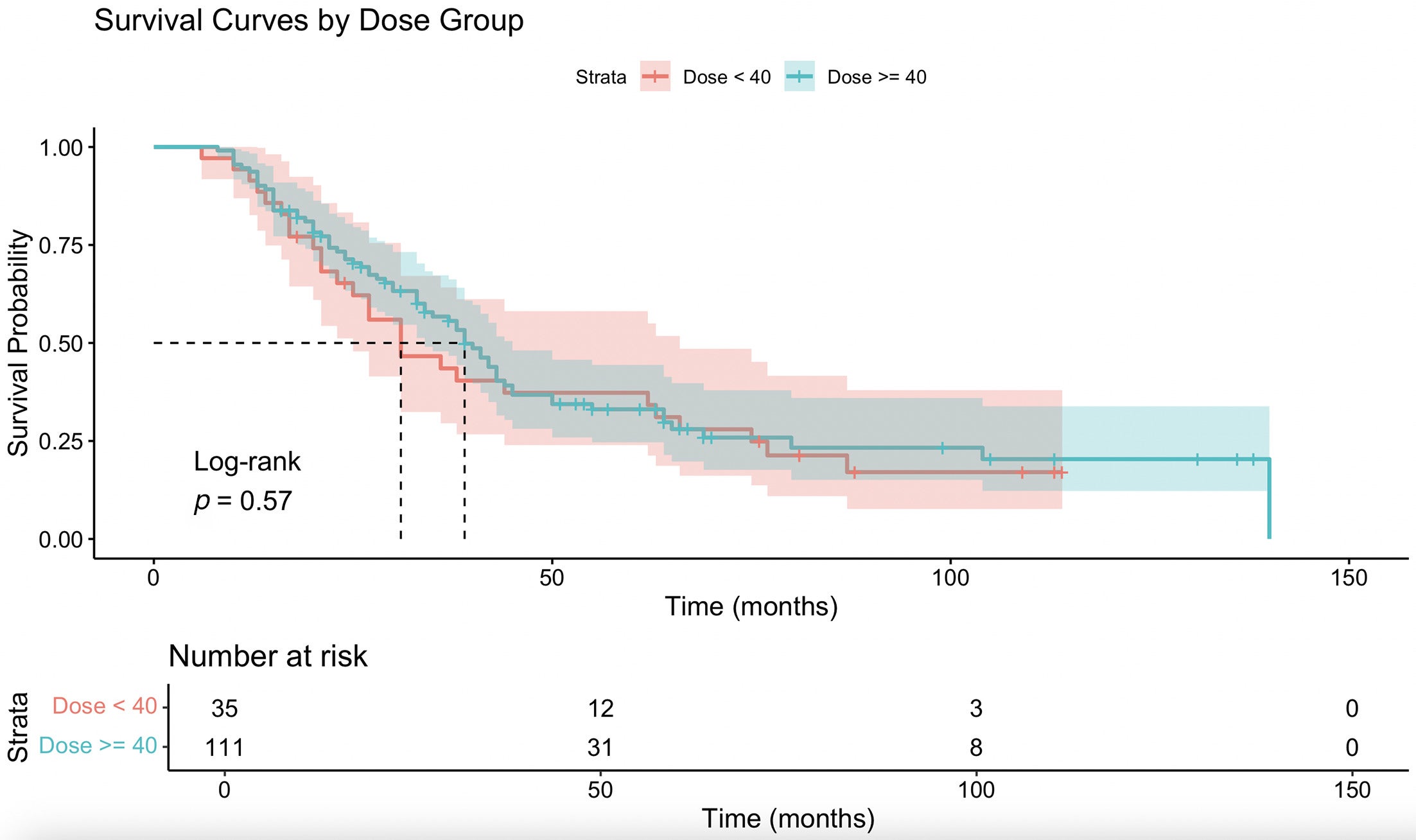

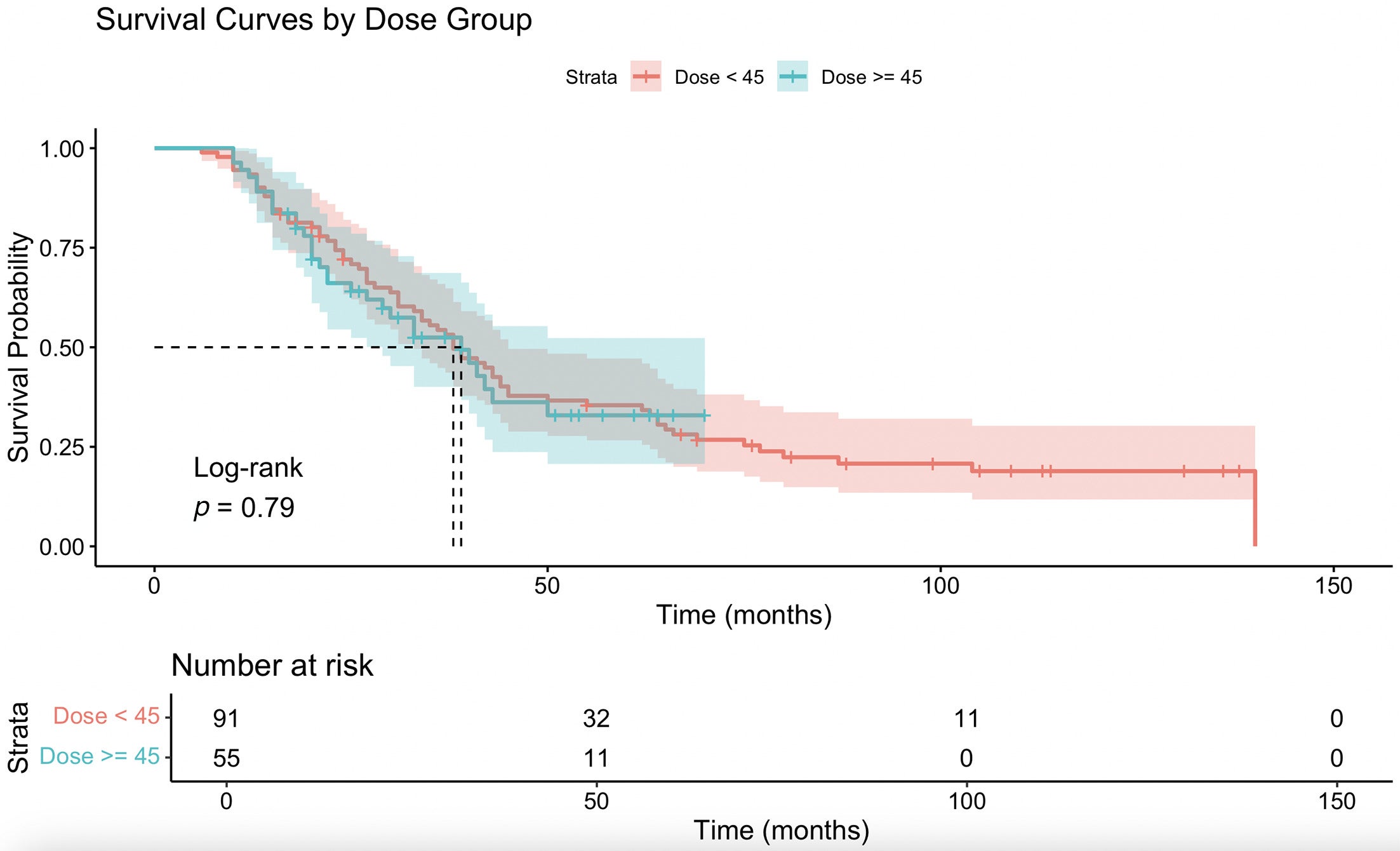

When the combined cohort was stratified by dose threshold, patients receiving ≥40 Gy had an insignificant difference in OS (HR = 0.881, 95% CI 0.564-1.377, P = .579), with insignificant survival curves ( Figure 4 ). There was also no significant association between ≥40 Gy and group 1 status (chi-square = 0.031, df = 1, P = .859; Fisher exact P = 1.000). Patients receiving ≥45 Gy had an insignificant difference in OS (HR = 1.064, 95% CI 0.684-1.654, P = .784), with a nonsignificant survival curve ( Figure 5 ). However, patients treated with ≥45 Gy were significantly more likely to have group 1 status postoperatively (chi-square = 5.412, df = 1, P = .020) and had higher odds of achieving group 1 compared with <45 Gy (OR = 2.458, 95% CI 1.060-5.783, Fisher exact P =.027).

Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing overall survival (months) between ≥40 and <40 Gy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing overall survival (months) between ≥45 and <45 Gy.

Within the tumor characteristics, there was a smaller proportion of patients with lymphovascular invasion when treated with ≥45 Gy; however, it was not significantly different than <45 Gy (chi-square = 2.638, P = .104, Fisher P = .113). Increased proportions of actionable somatic mutations and non-secretor status were noted as the IPSCAP group decreased ( Tables 1 and 2 ). Additional patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 .

Discussion

The optimal strategy for improving outcomes of patients with BRPC remains unknown and controversial. Meta-analysis has shown comparable OS outcomes between gemcitabine-based regimens and FOLFIRINOX as NAT in appropriately selected patients.23 Conflicting Alliance data show benefit of some NAT regimens incorporating CRT while no benefit with hypofractionation or low-dose SBRT.14, 24 Studies incorporating advanced radiation technologies such as MRI-guided SBRT delivering 50 Gy in 5 fractions have included resected patients with BRPC, reporting low rates of toxicity and encouraging 2-year survival.25

We previously reported our own experience with 26 resected patients who received ablative SBRT (median dose 50 Gy in 5 fractions) with no perioperative deaths in 90 days and an R0 rate of 96%.19 Our median progression-free survival from diagnosis was 13.2 months and median OS was not reached. The median time from the end of SBRT to resection was 50 days. Although the median dose translated to a BED of 100 Gy, the rate of postsurgical complications did not differ with historical controls, with an 8% rate of grade 1 pancreas anastomotic leak, grade 1 and 2 chyle leaks, grade 4 hemorrhage, and grade 2 wound infections. The rate of retroperitoneal abscess and grade 3 wound infection was 4%. In addition, the rate of postsurgical hospitalization did not differ from expected norms at our institution, with a median of 7 days. Thus, in our institutional experience, we have not observed increased perioperative complications after resection with ablative dose.

Although the desired outcome of treatment for patients with BRPC is prioritized as R0 resection, our IPSCAP data reveal improved pathologic outcomes, with lower scores suggesting a potential role for optimizing response strategies by including SBRT. Similar studies to this one on neoadjuvant treatment strategy for BRPC have been noted in the literature. Leung et al showed better local recurrence-free survival in patients treated with SBRT and chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone. Patients included in the SBRT group had more advanced baseline disease yet achieved significantly better post-treatment pathologic T stage, N stage, and perineural invasion, with similar OS.9 Results from Hill et al showed chemotherapy plus SBRT had no difference on OS vs chemotherapy alone but did have increased node negative, pathologic complete response, and negative margin resections in patients with locally advanced and BRPC.26 Zakem et al showed TRG 0 and 1 combined showed significantly increased OS (41 mo) compared with TRG 2 (25 mo) and 3 (24 mo).27

Based on the results of the present study, IPSCAP has validity as a robust postoperative multimodal pathology metric, and a very strong predictor of OS in patients treated with NAT incorporating 5-fraction ablative SBRT. Per-unit IPSCAP decrease is associated with a 23% decreased chance of death in patients with BRPC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and 5-fraction SBRT prior to resection. In addition, this study’s results provided insight into the differences in pathologic outcomes stratified by FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine-abraxane. FOLFIRINOX shows a superior survival with outcomes compared with gemcitabine-abraxane (HR = 0.742 vs HR = 0.804). Interestingly, our analysis also noted increasing proportions of actionable somatic mutations and non-secretors in lower IPSCAP groups. A similar study evaluating patients treated with chemotherapy and SBRT showed significantly better pathologic tumor regression grades in patients with KRAS mutations.28 Not all patients in our cohort received germline and somatic mutation testing, which limits comprehensive understanding of these impacts given that our study parameters included patients treated before routine institutional testing. Further studies incorporating these mutations into multivariate analysis may reveal the influence of genetic mutation status on IPSCAP and OS.

Our study raises significant questions about the correlation of ablative dose with IPSCAP. Our analysis shows that there is an increased achievement of lower IPSCAP group 1 in doses at or above 45 Gy. However, there is no OS benefit in this cohort. Doses of ≥45 Gy were only achievable in our department with the integration of the adaptive MRI linac technology, and only 37.7% of the patients included in this study received such treatment. With the MRI plans, we had daily confirmation of the GTV coverage and had the adaptive capability to optimize coverage if OAR tolerances were maintained. In addition, shortly after we instituted the MRI linac program, Hill et al published their data on the locoregional failure patterns in resected patients and advocated for including a generous clinical target volume (CTV).29 Accordingly, our GI Radiation Oncology physician group adopted this change in practice, routinely incorporating larger CTV volumes for treatment on the MRI linac. Thus, during the 10 years of this institutional experience, there was significant heterogeneity in the volume of GTV coverage to the prescribed dose, as well as the volume of the treatment field. Further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the question as to how ablative dose/volume escalation affects clinical outcomes for patients with BRPC, especially with the incorporation of uniform volumetric contouring as per the recent NRG consensus guidelines so that rigorous quality assurance can be maintained.10 Such studies should also carefully evaluate the contribution of dose to perioperative morbidity and toxicity, which was beyond the scope of this present 146 patient analysis. Future trials should integrate IPSCAP as a metric in order to further validate outcomes and serve as a valuable prognosticator for clinicians to measure patient response to treatment and evaluate higher-risk patients for tailored adjuvant therapies.

Limitations

This study was retrospective and conducted over a 10-year period reflecting differences in institutional treatment technology and contouring volumes that affected the prescribed dose. Lower doses were generally delivered before the incorporation of the MRI linear accelerator at our institution. As the study was retrospective in nature, it represents a heterogeneous patient population that may affect outcomes. Median OS calculations inherently include numbers that are derived from last contact, possibly lowering the reported median OS on more recent patients who may be still alive. Larger doses (ie, ≥45 Gy) were incorporated in this series with the integration of MRI-guided SBRT at our institution; thus, Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression are more reliable sources of OS interpretation vs median OS noted in the tables. In addition, low n values in group 3 may limit true interpretation of hazard risk among groups. GTV coverage to prescription dose increased with the MRI linac adaptive treatment capability due to real-time normal tissue accounting. This may positively influence postoperative pathology; therefore, the interpretation of dose impact on postoperative pathology should be considered. One patient had <2 u/mL CA-19-9 pre-treatment and 40.7 post-treatment and was labeled as a secretor.

Conclusion

Whether 5-fraction SBRT in addition to systemic chemotherapy improves the treatment outcomes of patients with BRPC is unclear at this time. Further prospective preoperative studies are needed to evaluate the impact of treatment-specific SBRT factors such as dose/volume escalation on clinical outcomes. This study suggests that IPSCAP incorporation is a reliable prognosticator in this setting and may be able to define high-risk patient populations that would benefit from tailored adjuvant therapies.