Assessing the Readiness for Climate Change Education in Radiation Oncology in the US and Canada

Affiliations

- Michigan State College of Human Medicine, Grand Rapids, MI

- University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA

- Northwestern University, McGaw Medical Center, Chicago, IL

- RUSH University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

- Princess Margaret Cancer Center, Toronto, ON

- MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX

- University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

- McGill University, Montreal, QC. †Ms. Silverwood and Dr. Lichter served as co-first authors and contributed equally to the work

Abstract

Objective:

Climate change poses significant challenges to health care, with radiation oncology being no exception. Educational gaps exist among radiation oncology professionals regarding the implications of climate change on patient care and health care delivery. This study aims to assess the perspectives of US and Canadian radiation oncology program directors (PDs) and associate program directors (APDs) on climate change education and its integration into residency programs.

Materials and Methods:

A survey was distributed to 114 PDs and APDs in the United States and Canada, focusing on attitudes toward climate change education, knowledge and beliefs about climate change and environmental sustainability, and perceptions of its impact on clinical practice. The final survey comprised 15 items, including a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), multiple-choice, and open-ended questions. Analysis of variance and post hoc least significant difference tests were used for data analysis.

Results:

Of the 114 individuals contacted, 36 responded (response rate 32%). Respondents rated the importance of incorporating climate change content into residency curricula at an average of 2 ± 1.2. Significant differences in attitudes were observed based on attendance at prior educational sessions on climate change ( P < .05); nonattendees rated the importance of this education lower, averaging 1 ± 0.0 vs 3.3 ± 1.0. Geographical analysis showed that 66% of Canadian respondents were in favor of integrating climate-related material into curricula compared with only 42% of United States counterparts ( P < .05).

Conclusion:

Despite varying interest levels and perceived relevance, the study underscores a need for enhanced climate change education in radiation oncology. It suggests exploring alternative educational avenues, such as continuing medical education and professional conferences, to address the challenges highlighted in this study. Incorporating climate change discussions into health care, particularly in training future radiation oncologists, is necessary for the field to adapt to and address the challenges posed by climate change.

Introduction

The need for medical professionals, including radiation oncologists, to receive education on climate change and its associated impacts on health care is becoming increasingly evident.1 The rise of extreme weather events linked to climate change is known to disrupt radiation therapy delivery through power outages, damage to crucial infrastructure, and interruptions in transportation networks, thereby adversely affecting patient outcomes, particularly in vulnerable groups such as the elderly and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.2 - 6 Furthermore, these climate-induced changes contribute to the proliferation of diseases and jeopardize essential resources like food and water supplies, as well as access to health care services.7 , 8 Recent studies have found that 80% of health care workers, including those in radiation oncology, are urging their employers to prioritize sustainable and environmentally conscious practices.9 However, 41% of physicians feel ill-prepared to discuss climate change with patients, highlighting a significant knowledge gap and emphasizing the urgency for educational initiatives in this domain.10

Efforts to incorporate climate change material into graduate medical education (GME) have been gaining traction across various fields nationally and internationally.11 - 15 In June 2019, the American Medical Association (AMA) released a policy statement supporting the inclusion of climate change content throughout GME.16 Despite the AMA’s support for such initiatives, a notable gap remains within the field of radiation oncology.17

Our aim was to evaluate the perspectives of US and Canadian radiation oncology program directors (PDs) and associate program directors (APDs) on climate change and sustainability education, as well as its impact on health care. Furthermore, this survey aims to identify both barriers and facilitators to implementing climate change education in these programs, potentially highlighting effective strategies for its incorporation. In doing so, this study seeks to foster a new generation of radiation oncologists who have the knowledge and skills to effectively address and adapt to the challenges climate change poses.18

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study focused on radiation oncology PDs and APDs in the United States and Canada. This group was chosen given their historical role in developing GME and continuing medical education (CME). The University of California San Francisco and Michigan State University Institutional Review Boards approved this study as exempt.

Survey Development

The survey was developed referencing published studies focusing on understanding perspectives on climate change and education initiatives.12 - 14 , 19 - 22 Survey questions fell into 3 main categories: climate change education and its integration into radiation oncology residency curricula, knowledge and beliefs about climate change and sustainability, and perceptions of climate change’s impact on clinical practice and patient care (see Supplementary Appendix below for details). Basic demographic information, including participants’ gender and location, was also collected. The survey was piloted with 10 experts in radiation oncology, education, and climate science to improve the clarity, relevance, and structure of the questions.

The final survey comprised 15 items, including a 5-point Likert-type scale, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions. The 5-point Likert-type scale, which ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), assessed 10 questions across 3 main categories detailed in the Supplementary Appendix below. Definitions of key terms were provided (see Supplementary Appendix below) to ensure a uniform understanding. The survey was emailed to 114 PDs and APDs in the United States ( n =101) and Canada ( n = 13). Participants were allotted 1 month to complete the survey, during which time 2 additional reminders were sent. No incentives were offered. The survey was administered through Qualtrics digital software version XM ©2020, and all data collected were anonymized. In accordance with institutional review board guidelines, participants were not obliged to answer every question.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation [SD]) were calculated to summarize the characteristics of participants and question responses. To investigate the differences in response patterns based on exposure to climate change education (not been offered sessions, have attended, offered but not attended), geographical location (United States, Canada), perceived importance of climate change and sustainability (low, moderate, high), and gender (male, female, other), multiple one-way analysis of variance (ANOVAs) were employed. For post hoc testing, the least significant difference (LSD) tests were conducted, considering the relatively small number of comparison groups in each analysis. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for statistical tests. All statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Software for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM).

Results

Demographics

Of the 114 PDs and APDs, 36 individuals responded to the survey for an overall response rate of 32%. Of these individuals, 21 (58%) were from the United States, 6 (17%) were from Canada, and 9 (25%) did not report their location ( Table 1 ). Within the United States, the Midwest (19%) was the most represented, followed by the Northeast and Southeast (14% each), and the West (11%). Notably, no responses were received from individuals in the Southwest, Hawaii, or Alaska. Among the participants, 24 (67%) were PDs and 3 (8%) were APDs, with 9 (25%) not specifying their role. Gender distribution varied, with 13 (36%) females, 11 (30%) males, 1 (3%) self-identifying, and another 11 (31%) choosing not to disclose gender.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents (n = 36)

| STUDY PARTICIPANTS | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Role | |

| Program directors | 24 (67%) |

| Associate program directors | 3 (8%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (36%) |

| Male | 11 (30%) |

| Self-described | 1 (3%) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (8%) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 5 (14%) |

| Southeast | 5 (14%) |

| Midwest | 7 (19%) |

| Southwest | - |

| West | 4 (11%) |

| Hawaii/Alaska | - |

| Canada | 6 (17%) |

Climate and Education

Overall, respondents did not agree that incorporating climate change (mean 2 ± SD 1.2) and sustainability (mean 2 ± 1.2) content into radiation oncology residency curricula is important. There, however, was moderate agreement that residents would be interested in learning these topics (mean 3 ± 1.1), while fewer perceived faculty would share this interest (mean 2 ± 1.1).

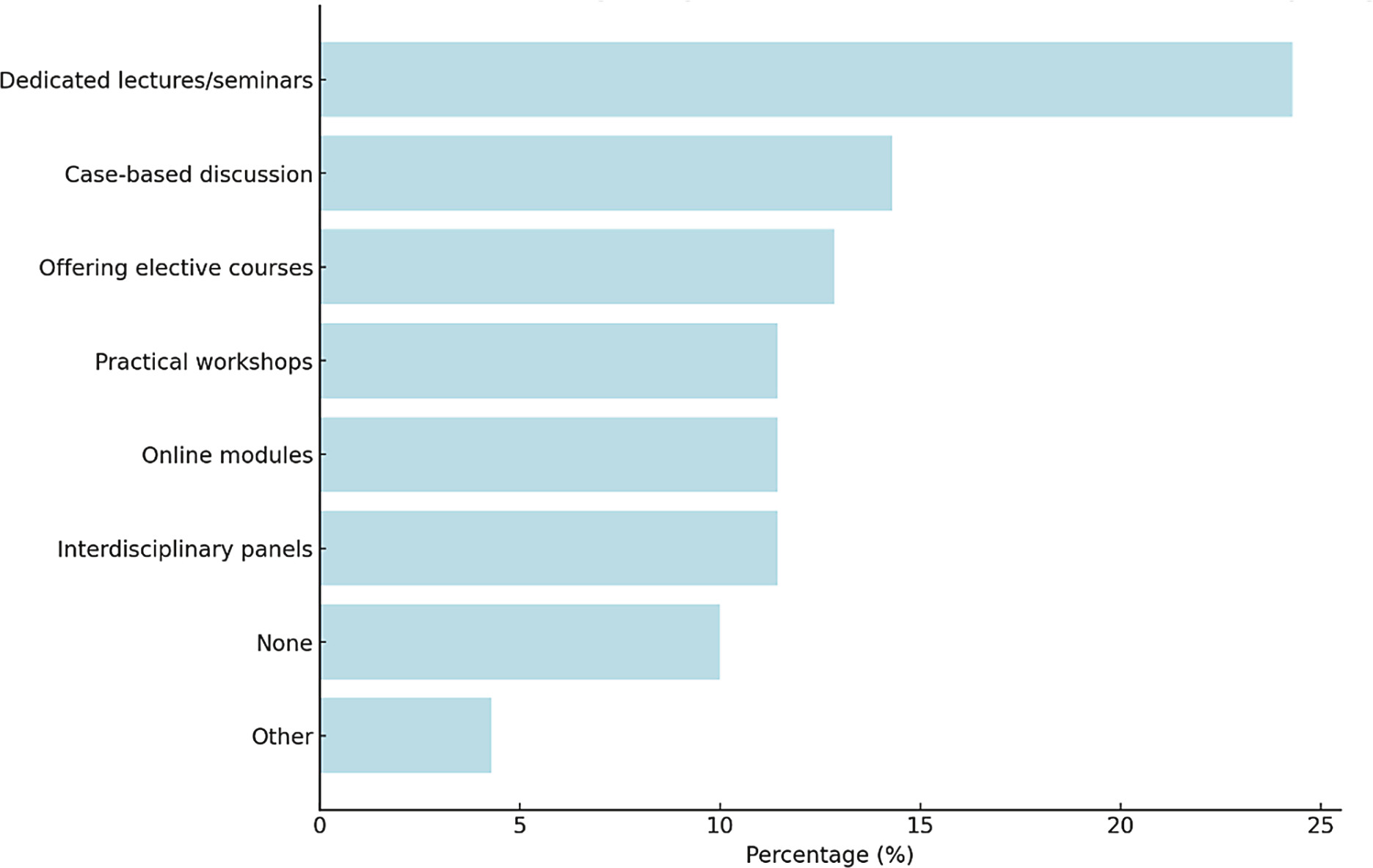

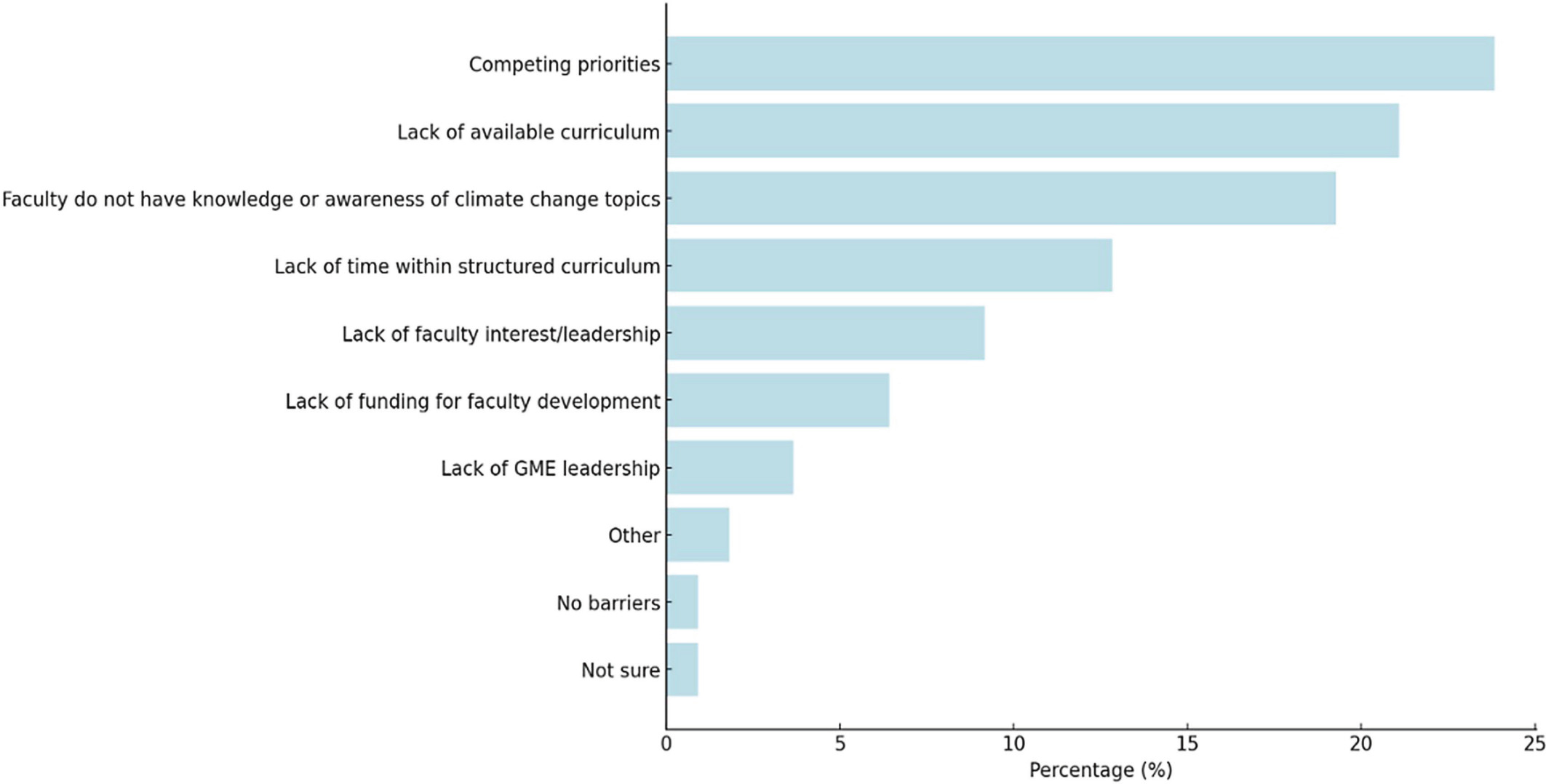

Respondents rated the most important educational topics in relation to climate change to be cancer (44%), food and water security (38%), and health disparities and inequities (30%). The preferred methods and challenges for incorporating climate health education are demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2 .

Preferred method for integrating climate health education into a residency program (n=36).

Respondent’s perceived barriers to implementing climate health and sustainability curriculum in radiation oncology programs (n = 31). Note that all individuals responded to this question. GME, graduate medical education.

Perceptions Around Climate Change

The survey revealed moderate agreement regarding the importance of climate change (mean 3 ± 1.2) and sustainability (mean 3 ± 1.3) for radiation oncologists. The relevance of climate change in addressing health equity also received a mean score of 3 ± 1.2.

Perceived Relationship Between Climate Change and Patient Care

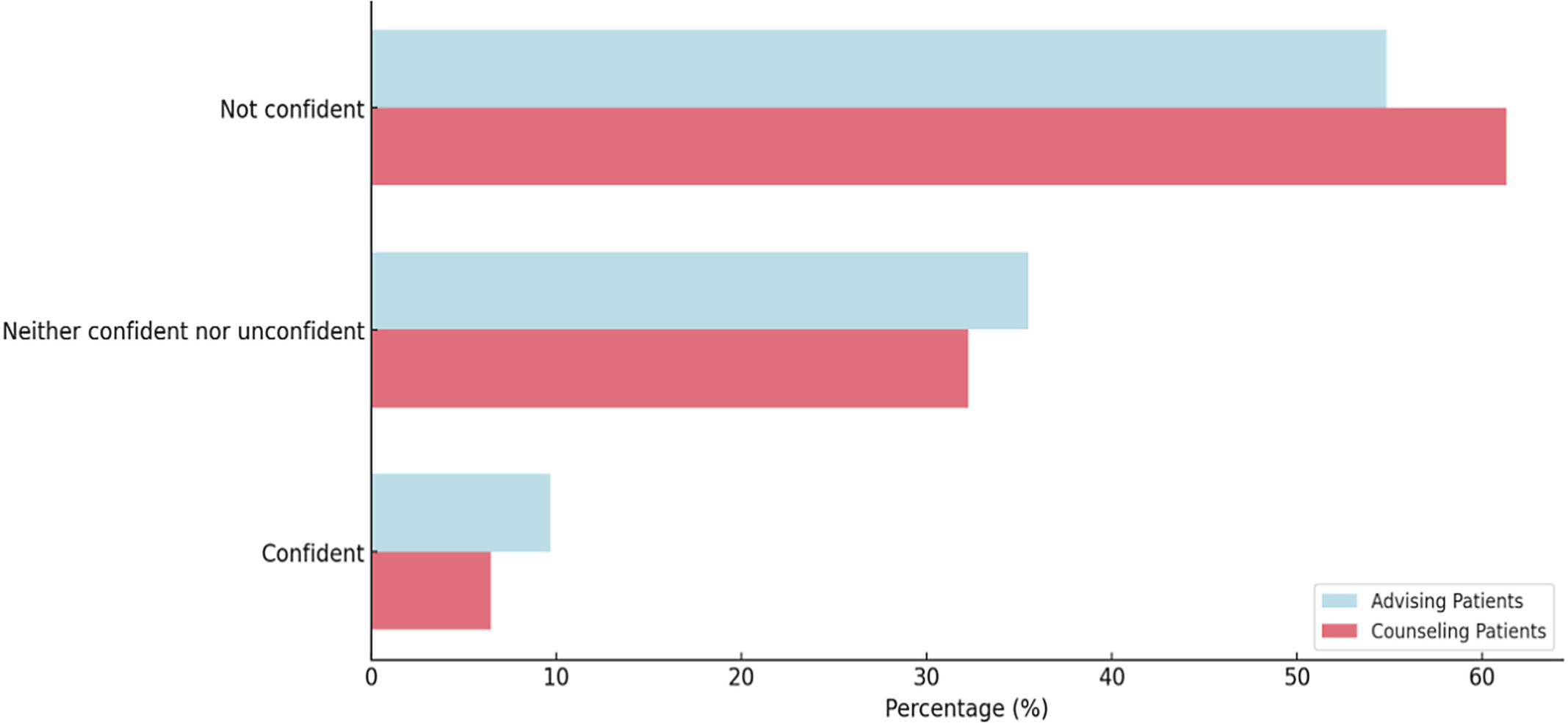

While acknowledging the impact of climate change on patients (mean 4 ± 1.1), most respondents doubted the necessity for radiation oncologists to discuss these issues with patients (mean 2 ± 1.5). Only 6% of respondents felt sufficiently prepared to counsel patients on the health impacts related to climate change, whereas 10% expressed confidence in advising patients on protecting themselves against climate-related health impacts (see Figure 3 ).

Confidence of program directors (PDs) and associate program directors (APDs) in counseling patients on the health impacts of climate change and advising them on measures they can take to protect themselves from climate change-related impacts (n = 31). Note that all individuals responded to this question.

Impact of Educational Sessions on Attitudes Toward Climate Change

Using ANOVA, significant differences were observed in attitudes toward climate change and sustainability curricula among groups defined by their participation in prior educational sessions ( P < .05). Key areas where notable disparities emerged included the perceived urgency of addressing climate change in residency curricula, the importance of sustainability in the practice of radiation oncology, willingness to incorporate related materials into educational curricula, and perceptions of faculty interest in these topics among PDs/APDs ( Table 2 ).

Median Scores and Standard Deviations for Likert Scale Responses From PDs/APDs (Scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) on Climate and Sustainability Survey Questions

| QUESTIONS | ALL RESPONDENTS n = 36 MEAN ± SD |

PRIOR EDUCATION n = 22 MEAN ± SD |

OFFERED EDUCATION, BUT DID NOT ATTEND n = 5 MEAN ± SD |

NOT OFFERED EDUCATION n = 4 MEAN ± SD |

P VALUE ( t TEST) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change is an important issue for radiation oncologists | 3 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± .9 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | .26 |

| Climate change is an important issue for addressing health equity | 3 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± .9 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | .37 |

| It is important to address climate change and its health impacts in the core radiation oncology residency curriculum | 2 ± 1.4 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± .0 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | .010 |

| Sustainability and health care decarbonization is an important issue for radiation oncologists | 3 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | .05 |

| It is important to address sustainability and health care decarbonization in the core radiation oncology residency curriculum | 2 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± .8 | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | .22 |

| Climate change currently impacts population health outcomes | 4 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± .4 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | .25 |

| It is important for radiation oncologists to bring the health impacts of climate change to the attention of their patients | 2 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± .8 | 1.2 ± .4 | 2.7 ± 1.6 | .12 |

| I would be willing to make time in the curriculum to discuss climate change and sustainability if educational materials were provided | 2 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± .0 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | .01 |

| I believe residents would be interested in learning more about climate change and its health impacts | 3 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± .8 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | .35 |

| I believe other faculty, in addition to residents, would be interested in learning more about climate change and its health impacts | 2 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± .8 | 1.4 ± .5 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | .01 |

Abbreviations: APDs, associate program directors; PDs, program directors; SD, standard deviation.

Bolded values are statistically significant.

Comparative Analysis Based on Session Attendance

Further investigation with post hoc LSD tests (a method used to find differences between group means) showed significant differences among 3 groups: those who attended educational sessions on climate change, those who were offered but did not attend, and those who were not offered any education on the subject ( P < .05). Specifically, participants who had not been exposed to education on climate change demonstrated significantly lower levels of acknowledgment regarding the importance of climate change and sustainability within their professional domain.

Perceptions of Climate Change and Sustainability

Similarly, the study revealed that recognizing the significance of climate change and sustainability affects various perceptions, such as equity in responses, the urgency of incorporating these topics into residency curricula, the fundamental importance of sustainability, and the necessity for radiation oncologists to engage in discussions about these issues with patients ( P < .05). Further analysis using post hoc LSD tests showed that those who deemed climate change and sustainability important were also more likely to express concern about related topics.

Perceptions Across North America

Finally, the impact of location (Canada vs the United States) on responses was evaluated using chi-square analysis. A higher percentage of Canadian respondents, compared with their United States counterparts, indicated a willingness to integrate climate-related material into residency curricula if such material was provided (66% vs 42%, P < .05). However, for the other questions posed in the study, there were no significant differences in responses between the 2 groups.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the attitudes and opinions of radiation oncology PDs and APDs in the United States and Canada regarding the integration of climate change education into radiation oncology GME. This investigation is particularly timely, given the growing recognition of climate change’s impact on health care delivery and patient outcomes, especially in specialized fields like radiation oncology. The broader trend toward environmental consciousness in health care, as demonstrated by findings from a national study, highlights the importance of incorporating climate change education and sustainability practices into radiation oncology curricula, aligning with the evolving priorities of medical professionals across the nation.9

A significant finding from this study is the discrepancy between the recognized importance of climate change impacts on patient health and the low priority given to integrating climate change content into radiation oncology residency curricula. This divergence suggests a gap between awareness and action within the field. The AMA’s support for climate change education, echoed by organizations like the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) and American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO), contrast with our findings of a tepid interest from RO educational leaders (PDs and APDs), underscoring the need for a broader cultural shift within the specialty.16 , 23 , 24

Notably, the study revealed that those with prior education or acknowledgment of the significance of climate change were more likely to integrate this knowledge into their medical practice, including finding opportunities to reduce their own “clinical footprint.” However, the survey did not detail the nature of this prior education—such as venue (eg, conferences or CME), format (online or in-person), timing, or session quantity. Despite this, given the wide range of educational opportunities offered by numerous institutions, from formal lectures to informal discussions, the authors inferred that respondents may have participated in such activities.25-27 This finding suggests that the route to incorporating climate change education into radiation oncology may lie in alternative educational avenues outside the traditional GME structure. CME programs, for instance, could offer targeted courses linking climate change and radiation oncology, as evidenced by previous successful programs.25 - 28 Conferences also provide an expansive platform for workshops, lectures, and panel discussions. Furthermore, the success of platforms like the Radiation Oncology Education Collective Study Group (ROECSG) and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Radiation Oncology (DEIinRO) in delivering accessible, customized educational content indicates a promising avenue for disseminating information on climate change and radiation therapy.29 , 30

However, the integration of climate change education into GME remains a crucial long-term objective. The disproportionate impact of climate-related events, such as wildfires, on vulnerable populations and the subsequent exacerbation of health care disparities highlight the urgent need for comprehensive training in this area within oncology.2 , 6 , 31 Such education would not only inform residents about the interplay between environmental factors, public health, and social equity but also empower them to make environmentally conscious decisions in their future clinical practices. Nevertheless, the barriers to implementation highlighted by the survey, such as competing priorities and the need to train and provide educational material to faculty, must be acknowledged and addressed. One approach to bridge these gaps could be the integration of new materials into supplementary didactic sessions rather than embedding them directly into the core radiation oncology curriculum. This strategy could help manage the challenge of overburdening the core curricula while still educating residents on the importance of these topics. Potential pathways for such integration could involve collaboration with professional radiation oncology bodies, educational committees, or accreditation organizations to develop and disseminate such material. The existence of third-party organizations, such as Climate Resources for Health Education (CRHE)32 , which are already dedicated to providing educational materials for health care professionals, could facilitate this process and lessen the burden on institutions to develop new content.

The study is subject to several limitations, such as potential response bias and inadequate geographical representation. Certain confounding factors and historical elements, such as regional susceptibilities to climate events, add additional complexity to interpreting the presented data regarding patient vulnerability to climate-related interruptions of care. Additionally, the results may be influenced by social desirability bias, with respondents possibly overestimating the importance of climate change to align with perceived socially acceptable views. The inability to thoroughly analyze the impact of location on survey responses because of the small sample size as well as the structure and phrasing of the survey may both bias responses and limit the interpretation of the findings. Finally, while the response rate is low and limits the generalizability of our study, it is comparable to other studies on this topic.10,12-14 Despite these limitations, the findings offer meaningful insights from leaders in radiation oncology education, shedding light on both the facilitators and obstacles to integrating climate change education within the field. In response to the feedback received, we recommend future surveys specifically address the nuances of integrating climate change topics into the core radiation oncology curriculum. This could involve a careful distinction between the addition of discrete didactic sessions and the broader implications of embedding such content as a core component, thereby ensuring a more nuanced understanding of stakeholders’ willingness and the practical challenges involved.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the study indicates a degree of reluctance within the radiation oncology community to prioritize climate change education, it also points to alternative pathways and the need for a multifaceted approach to incorporate this critical subject into the curriculum. The integration of climate change discussions into health care education, particularly in specialties like radiation oncology, is not just a matter of academic interest but a necessity to prepare health care professionals for the challenges posed by a changing climate. Through dedicated efforts to embed these topics into medical training, there is an opportunity to shape a generation of radiation oncologists who are not only skilled clinicians but also informed and proactive in addressing environmental challenges and the associated impact on patient care.

References

Supplementary Appendix

Survey Questionnaire

- For this question, please indicate your answer based on how strongly you agree or disagree with the following statements. For the purpose of this question, please refer to the definitions below:

- Climate change is defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency as, “any significant change in the measures of climate lasting for an extended period of time. In other words, climate change includes major changes in temperature, precipitation, or wind patterns, among other effects, that occur over several decades or longer.”

- Sustainability is defined by the United Nations Brundtland Commission as, “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

- Decarbonization is defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency as, “[the] process of reducing Greenhouse gas emissions (eg, carbon dioxide).”

|

|

[1] |

[2] |

[3] |

[4] |

[5] |

|

1a. Climate change is an important issue for radiation oncologists. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1b. Climate change is an important issue for addressing health equity. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1c. It is important to address climate change and its health impacts in the core radiation oncology residency curriculum. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1d. Sustainability and healthcare decarbonization is an important issue for radiation oncologists. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1e. It is important to address sustainability and healthcare decarbonization in the core radiation oncology residency curriculum. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1f. Climate change currently impacts population health outcomes. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1g. It is important for radiation oncologists to bring the health impacts of climate change to the attention of their patients. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1h. I would be willing to make time in the curriculum to discuss climate change and sustainability if educational materials were provided. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1i. I believe residents would be interested in learning more about climate change and its health impacts. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

1j. I believe other faculty, in addition to residents, would be interested in learning more about climate change and its health impacts. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

- Does your residency curriculum include lectures or seminars on climate change and its health impacts?

- No, and there is nothing planned

- No, but I am planning to include lectures/seminars on this topic in the next 2 years

- Yes, less than 2 hours/year

- Yes, 2-4 hours/year

- Yes, more than 4 hours/year

- How do you think climate health education could be most effectively integrated into residency programs? Please select all that apply.

- Dedicated lectures/seminars

- Case-based discussion

- Practical workshops

- Online modules

- Offering elective courses specifically focused on climate health

- Interdisciplinary panels

- None

- Other (please specify): __________________________________________________

- What do you perceive to be the main barriers when implementing a curriculum on climate health and sustainability? Please select all that apply.

- Faculty do not have knowledge or awareness of climate change topics to help implement curriculum.

- Lack of available curriculum on climate change relevant to residents

- Competing priorities (climate change won’t directly impact my residents as much as other topics)

- Lack of time within structured curriculum

- Lack of funding for faculty development

- Lack of faculty interest/leadership

- Lack of GME leadership

- No barriers

- Not sure

- Other (please specify):__________________________________________________

- Please rank the three most important health consequences of climate change that residents should receive education with 1 being the most important.

______ Cancer

______ Cardiovascular disease

______ Environmental justice

______ Food and water security/scarcity

______ Health impacts of extreme weather events

______ Health consequences of air pollution

______ Health disparities and inequities

______ Heat-related illness

______ Impacts of severe weather

______ Infectious disease

______ Mental health impacts

______ Population displacement

______ Respiratory conditions

______ None

______ Unsure

______ Other

- Have you previously participated in an educational session addressing the health-related impacts of climate change?

- No, such sessions have not been accessible to me

- No, I have opted not to attend

- Yes, I have attended

- Are there measures being taken to reduce the greenhouse emissions (i.e. carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane) and decarbonize your program's hospital/ clinic?

- No, and no actions planned

- No, but there are plans to do so

- Yes

- I don’t know

- 7a. What measures being taken to reduce the greenhouse emissions (i.e. carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane) and decarbonize your program's hospital/ clinic? Please select all that apply.

- Reducing faculty/trainee travel (e.g. interviews, conferences, etc.)

- Encouraging the use of telemedicine to reduce travel related emissions

- Recycling

- Providing incentives for greener transportation (e.g. carpools, shuttles, cycling)

- Other __________________________________________________

- 7b. Do you think measures should be taken to reduce the greenhouse emissions (i.e. carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane) and decarbonize your program's hospital/ clinic?

- No

- Not sure

- Yes

- In your practice, have you observed any impact of climate change on your patients?

- No

- Not sure

- Yes

- How confident do you feel in counseling patients about the health impacts of climate change?

- Not confident

- Neither confident or unconfident

- Confident

- How confident are you in advising patients on protecting themselves from climate change-related impacts, such as extreme weather events (e.g., heatwaves, wildfire smoke, floods, etc.)?

- Not confident

- Neither confident or unconfident

- Confident

- If would like to provide any additional thoughts on climate change and its incorporation into the radiation oncology resident curriculum, please respond below:

________________________________________________________________

- Are you interested in participating in the development and testing of a curriculum on the health-related impacts of climate change? If so, please provide your contact information

- Yes __________________________________________________

- No

- What is your role?

- Program Director

- Associate Program Director

- In which region is your program located?

- Northeast (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York)

- Southeast (Washington DC, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Delaware, Maryland, Florida, Louisiana, and Arkansas)

- Midwest (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota)

- West (California, Colorado, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Washington)

- Southwest (New Mexico, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Texas)

- Alaska

- Hawaii

- Canada

- To which gender identity do you most identify?

- Male

- Female

- Non-binary

- Prefer not to say

- Prefer to self-describe

Citation

Silverwood SM, Lichter KE, Stavropoulos K, Pham T, Randall J, D’Souza L, MSc, Malik N, Croke J, Gunther JR, Cao J, Alfieri J, Mohamad O, Golden DW, MHPE, Braunstein S. Assessing the Readiness for Climate Change Education in Radiation Oncology in the US and Canada. Appl Radiat Oncol. 2024;(1):15 - 22.

doi:10.37549/ARO-D-24-00007

March 1, 2024